Artist Statement

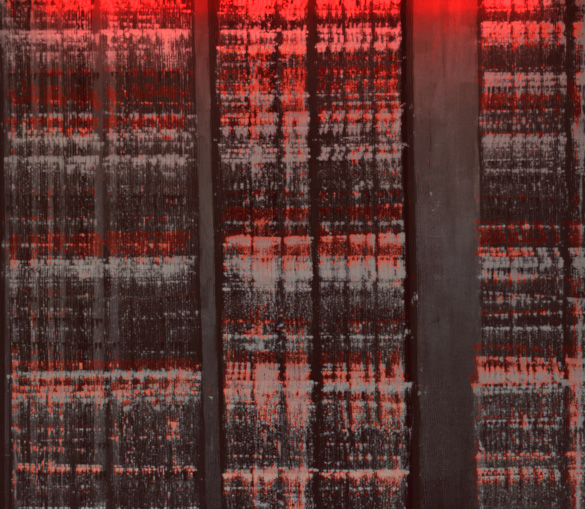

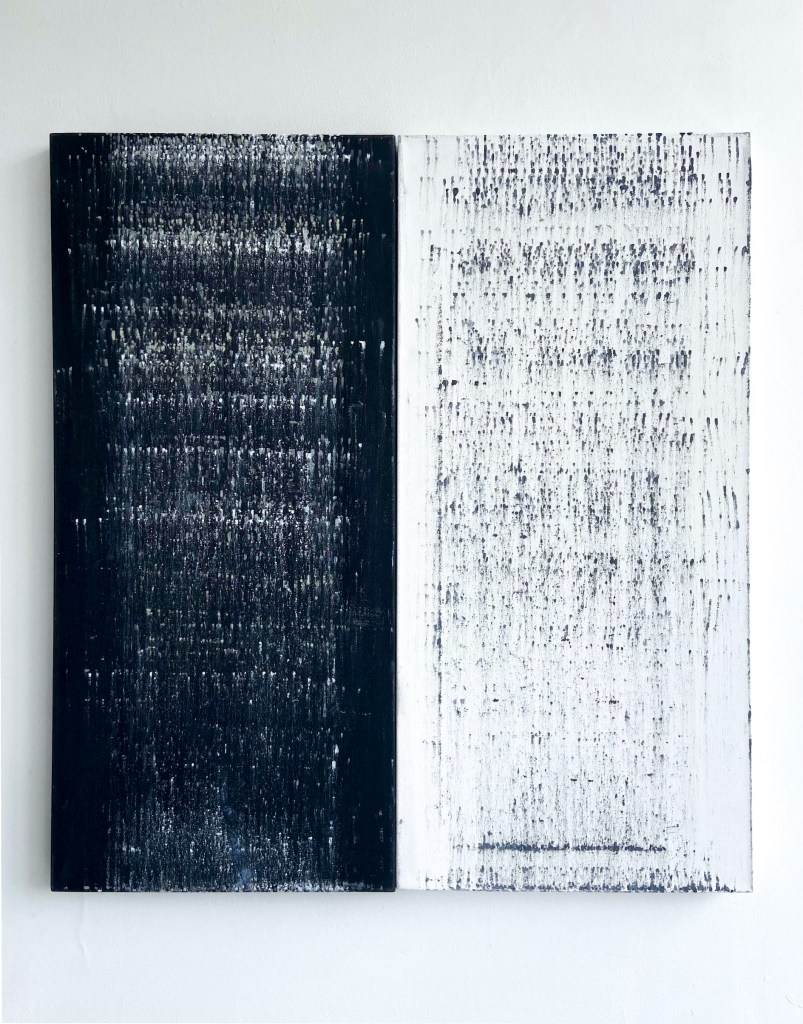

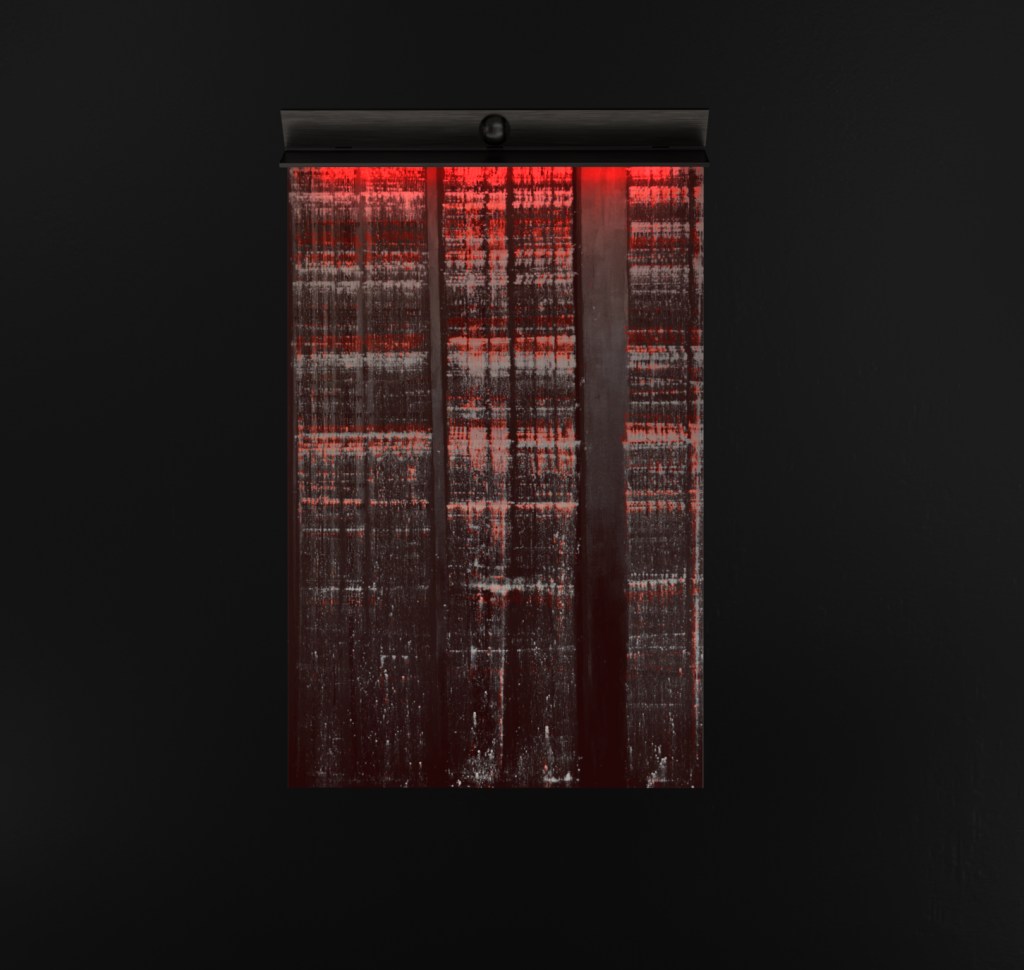

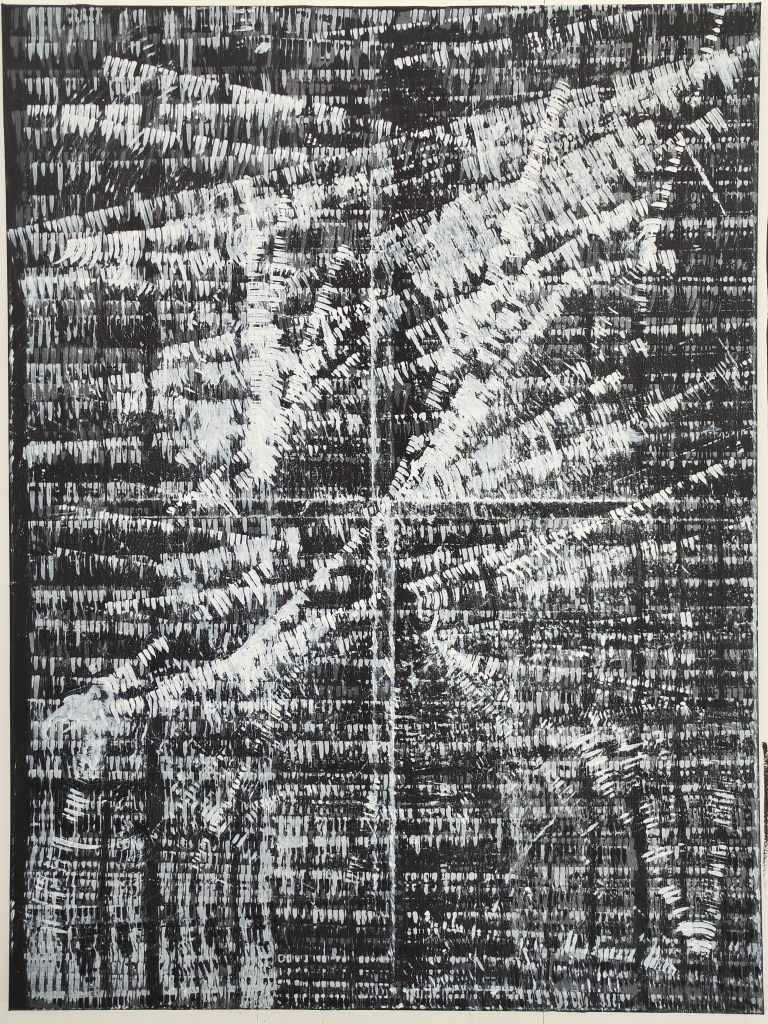

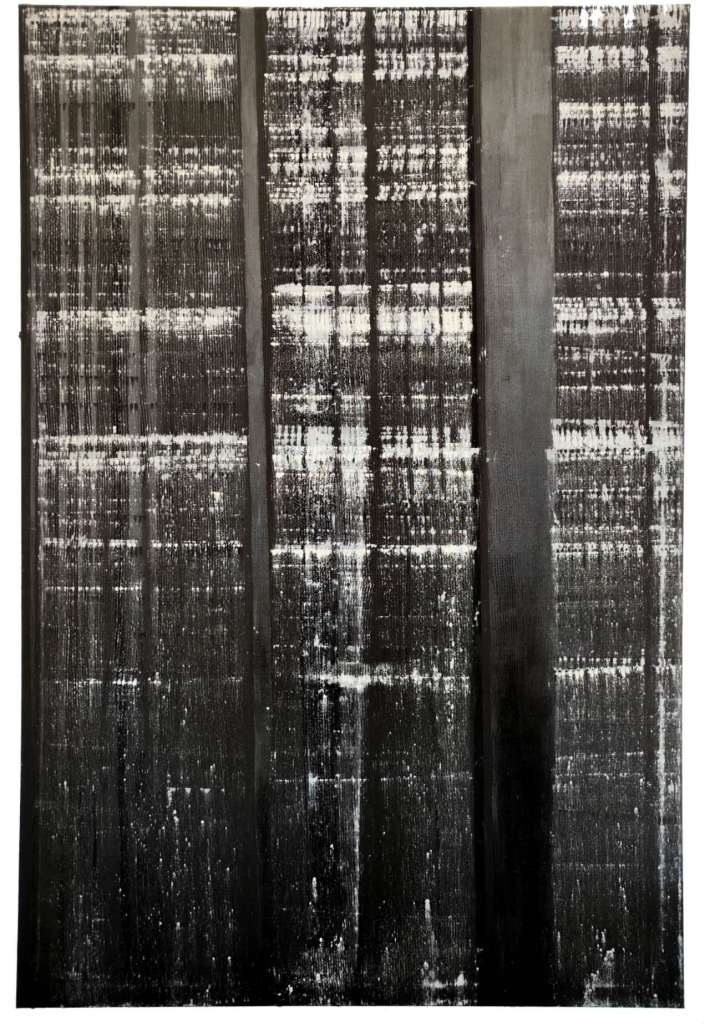

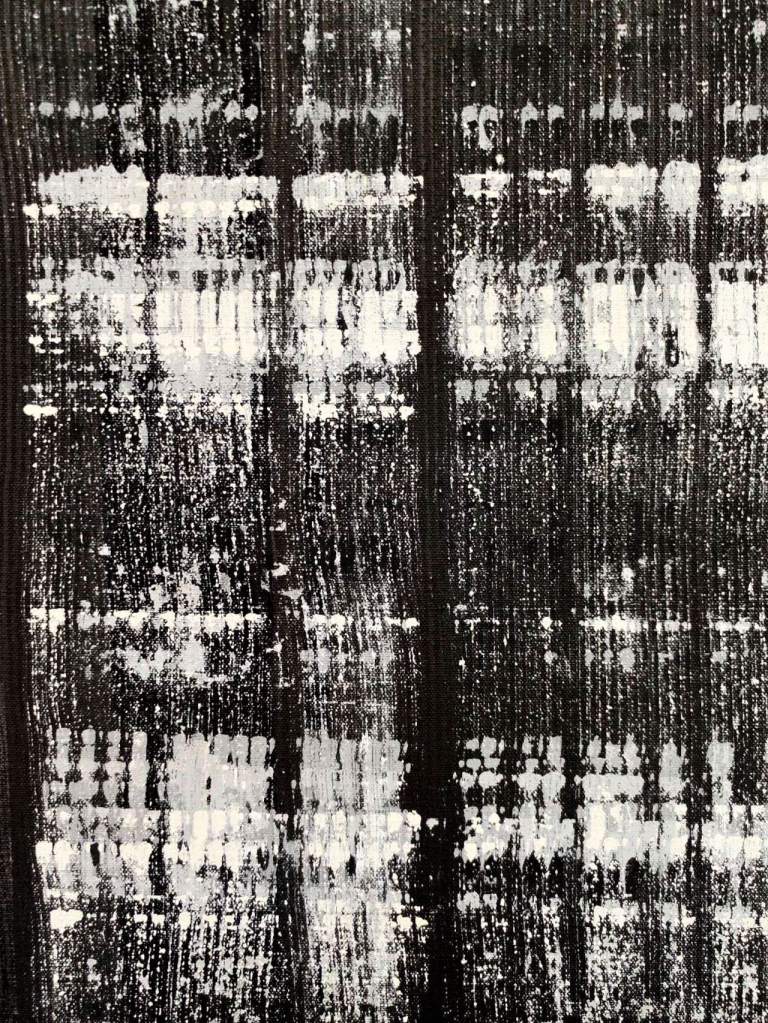

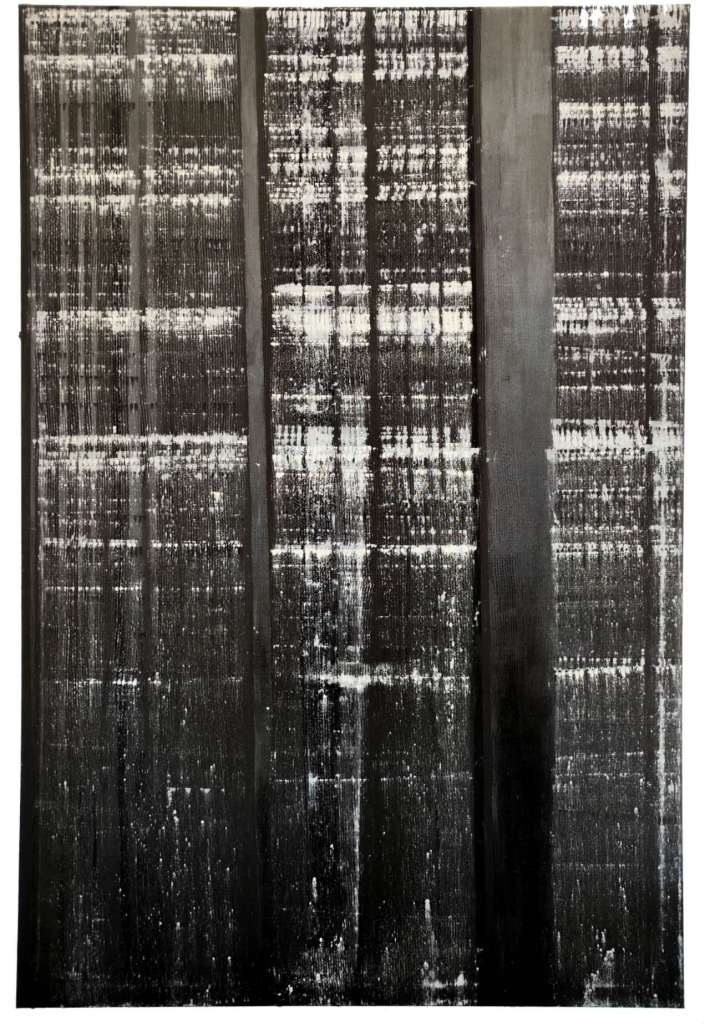

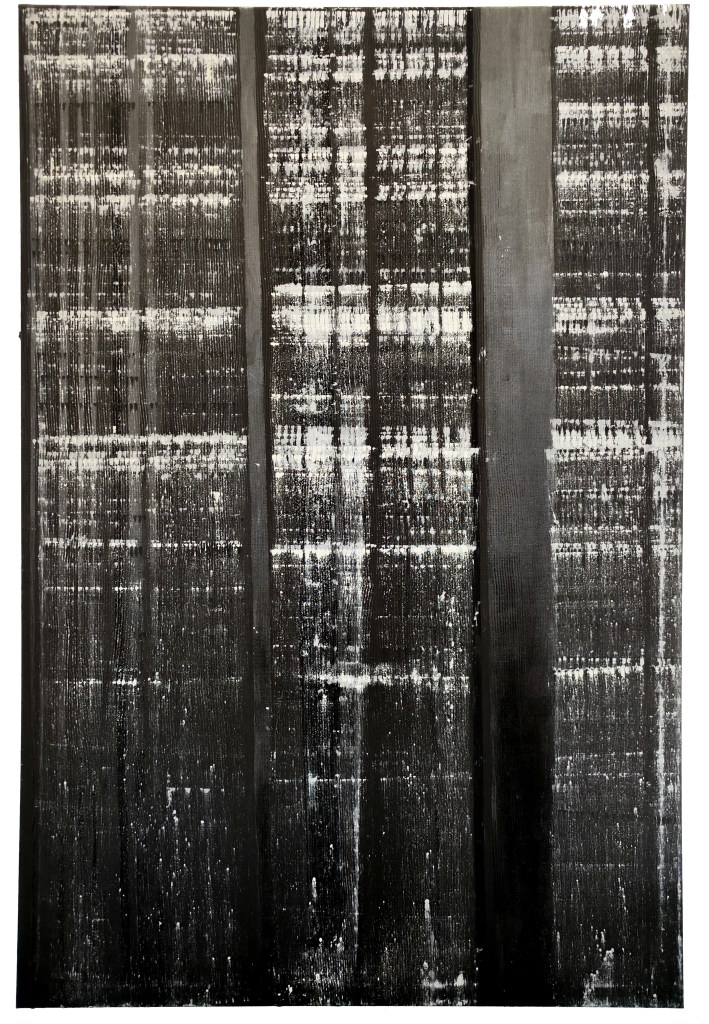

The 0/1 Series is a process-led body of work that translates digital language into physical gesture. Each piece begins with a word—such as produce or consume—converted into binary code (0s and 1s). Using a custom 3D-printed brush, where narrow and wide teeth represent these digits, I “print” the encoded patterns onto black canvas. Through this repetition, I become a living machine, transforming data into pigment, gesture, and pressure.

The works stem from my interest in how digital technology reshapes human cognition, behaviour, and perception. Influenced by Paul Virilio’s dromology and Hartmut Rosa’s theory of social acceleration, I see painting as a way to reintroduce friction into a culture obsessed with speed and smoothness. Each mark carries both resistance and delay—a tactile counterpoint to the frictionless logic of the algorithmic world.

Rosa Menkman’s glitch aesthetics inspired my methodology of “revelation”—to make the hidden systems of control perceptible through material deviation rather than digital simulation. In this sense, the 0/1 Series is not about error, but exposure: it renders visible the structures we no longer see.

Painting, for me, becomes a site to reclaim embodied presence—where the slow, resistant process of mark-making restores a sense of human agency within an increasingly automated visual world.

Art practice & Documentation

The creative practice in recent experience builds upon the theoretical and methodological foundation established in previous chapter, further expanding my exploration of Rosa Menkman’s notion of Constructive Glitch—the idea of revealing inner structures through error or breakdown, uncovering what has become so habitual that it turns invisible. This act of revelation became a central methodology throughout my series of works in this unit.

In the following reflection, I attempt to trace the development of my artistic journey across the MA course, mapping how my conceptual thinking and material approaches have evolved.

At the beginning, my focus on the theory of social acceleration led me to explore tensions between speed and stillness—between rapid, dynamic gestures and slow, deliberate strokes. I sought to express the human condition under technological progress: the transformation of people from users of technology into its very fuel. As Paul Virilio asserts, “You don’t have speed, you are speed.” My early paintings were primarily concerned with the visual tension generated by such contrasts — the collision of velocity and resistance — and I was captivated by their surface effects. However, I had not yet reflected deeply on the materiality of the image or the performative dimension of painting itself.

Later, encountering Fabian Marcaccio’s Technobrutalist Portrait (2020–2022) redirected my attention back to the material autonomy of painting. His approach prompted me to reconsider the subtle parallel between the relationship of the artist to the artwork and that of humans to technology. Around this time, I wrote a short essay examining the notion of artistic materiality [Read More…], where I discussed Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe’s view of the technological sublime: that technology is both a product of human knowledge and an entity beyond human control. Although my focus then remained on the completed artwork as something that escapes the artist’s grasp at the moment of its “completion,” this reflection laid the conceptual foundation for what later became my process-led abstract painting practice.

In the middle stage of my MA, my perspective shifted—from what kind of image I wanted to produce, toward what kind of action or process could generate that image, and what meaning that process might embody. As my process continued, I began to wonder whether the act of revelation—central to my glitch-based practice—could be materialised not only through pigment but through the physical properties of light itself. This question led me to experiment with creating my own tools.

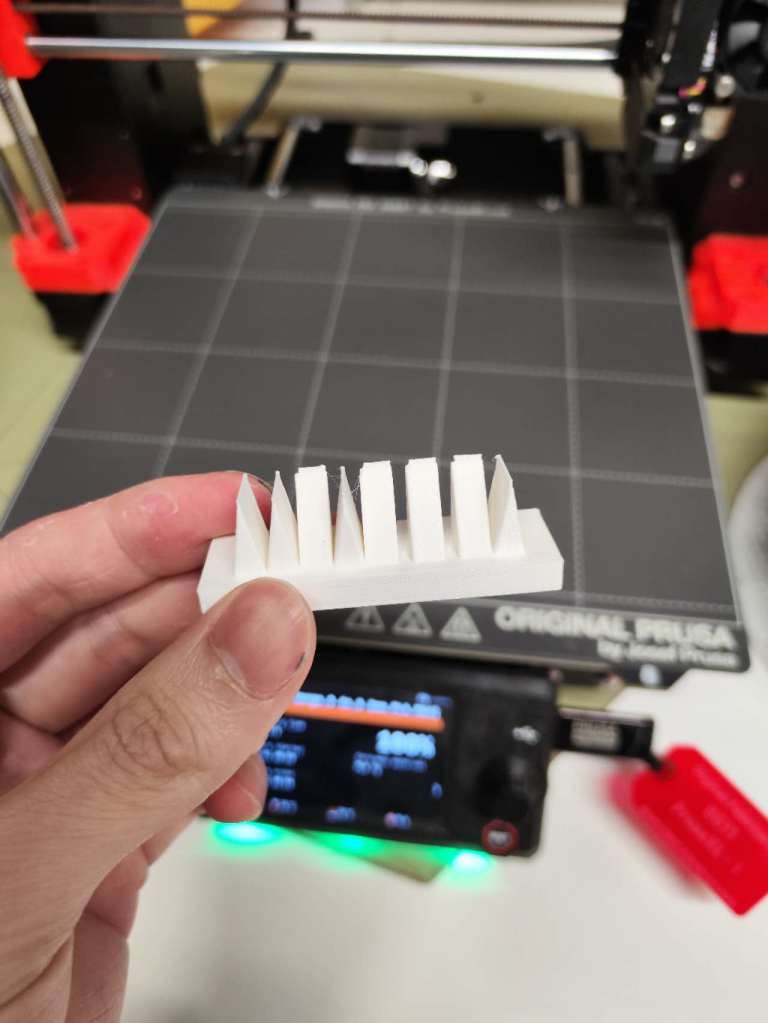

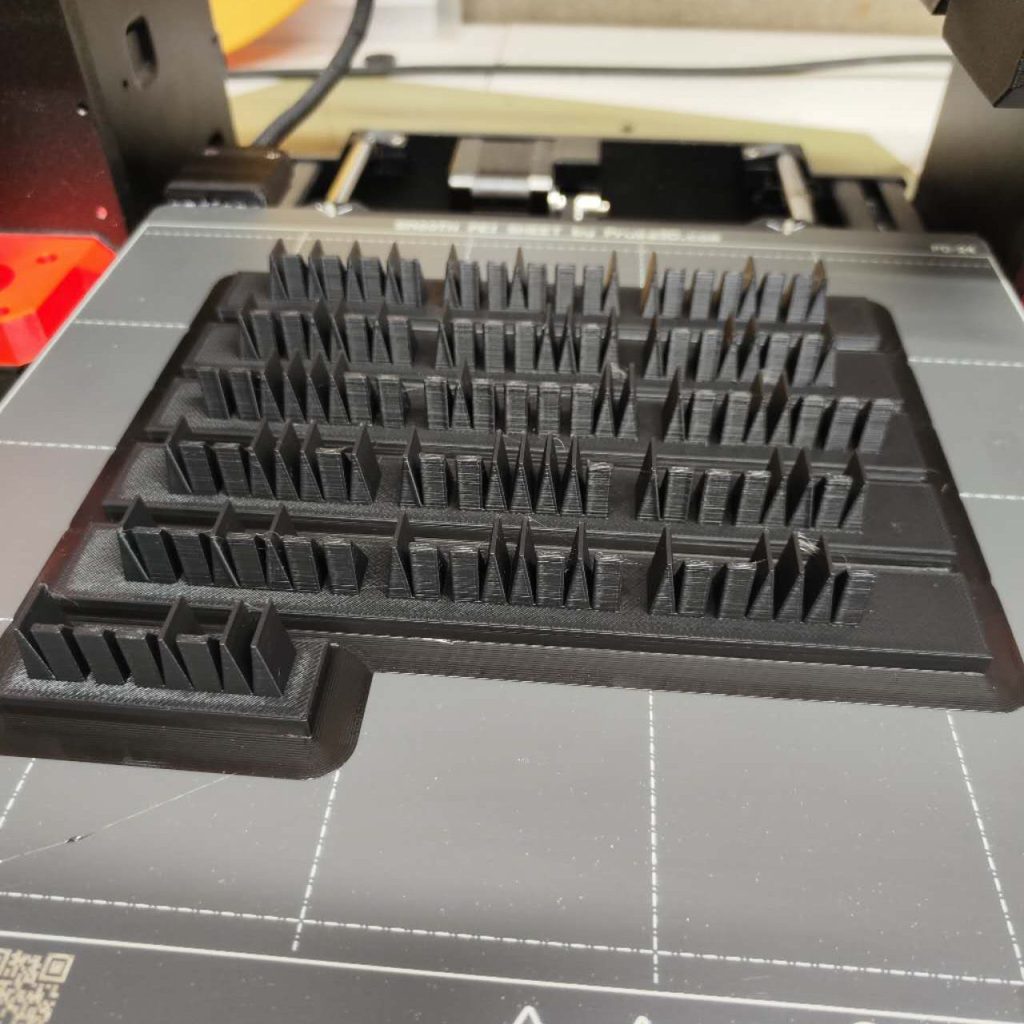

Combining this inquiry with my ongoing research into digital media, I designed a custom brush that itself carries information. Each brush was constructed from binary code: I converted selected words into sequences of 1s and 0s, and each binary digit was translated into a physical form—1 as a wide 3D-printed tooth, 0 as a narrow one. This transformation echoed Marshall McLuhan’s assertion that “the medium is the message.”

My choice of binary code was not purely formal but conceptual. Every tweet, message, or image we share online is encoded into countless 0s and 1s. The platforms that transmit, receive, and process these data create an experience of seamless frictionlessness—a user interface that accelerates access to information while also accelerating the spread of misinformation. As users, our critical discernment is dulled by the automation of scrolling and consumption.

My practice aimed to subvert this “UI/UX logic” of frictionless exchange. I sought to reintroduce resistance—to make every act of reading and input carry a cost. By exposing familiar linguistic forms as combinations of 0 and 1, I rendered them opaque and estranged, echoing Viktor Shklovsky’s notion of ostranenie (defamiliarization): the disruption of automatic perception. In a technological context, this became a disruption of the habitual digital browsing experience—the endless, automated timeline scroll.

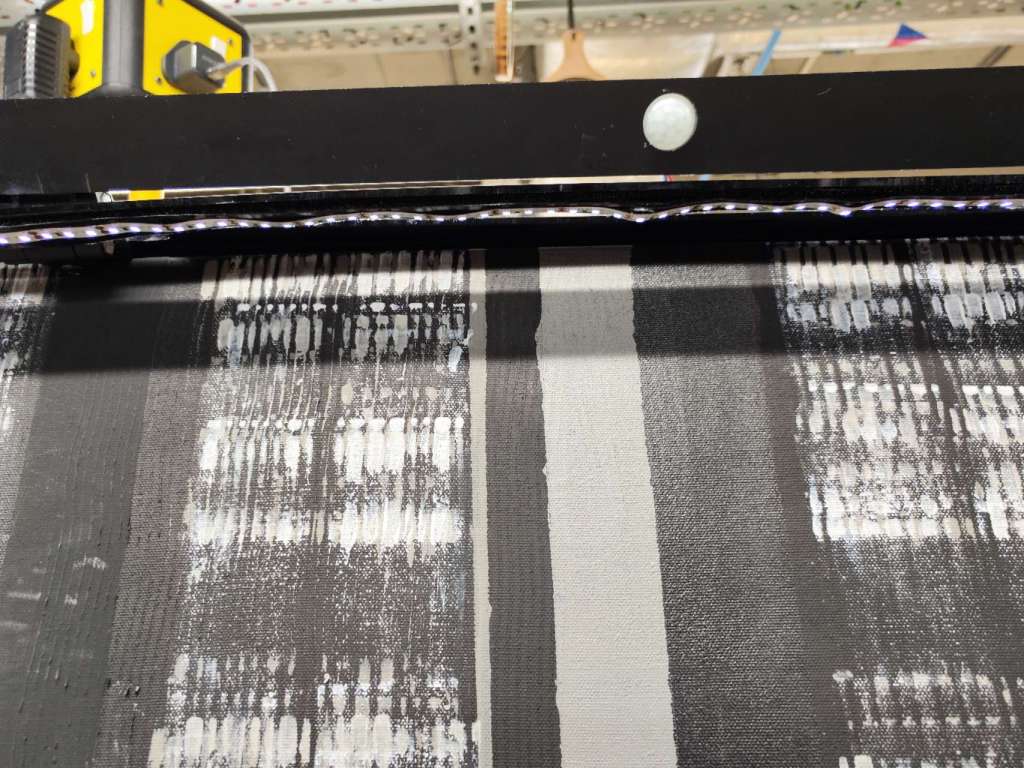

Thus, my strategy of revelation was no longer about producing visual tension between fast and slow gestures, nor about simply aestheticizing the glitch as Menkman describes. Instead, I attempted to reconstruct it from within the system’s logic. Using my binary brush, I loaded white paint and repeatedly “printed” the encoded marks onto black canvas. In this process, I became a living machine—performing an act of data inscription. Painting itself turned into a ritual: transforming the everyday digital act of typing, sending, and posting into a physical, resistant gesture.

Communication was no longer expressed through recognizable language but through the binary substrate beneath it. Each stroke embodied both pigment and pressure, both intention and mechanical repetition. The act of “sending” became a sequence of bodily transmissions—manual yet systematic, imperfect yet rhythmic. The resulting surfaces resembled malfunctioning CRT displays: flickering, dense, and glitch-like. But the “error” here was not simulated through digital effects; it was produced by the human body itself—through tremor, fatigue, and micro-variations of force.

In the later phase of my practice, I began to question whether this ritual of painting could extend beyond traditional materials—beyond acrylic pigment and linen canvas. Inspired by my previous research on light-based artists such as James Turrell, I became interested in incorporating light as both material and metaphor, situating the act of painting more directly within the field of digital and technological media.

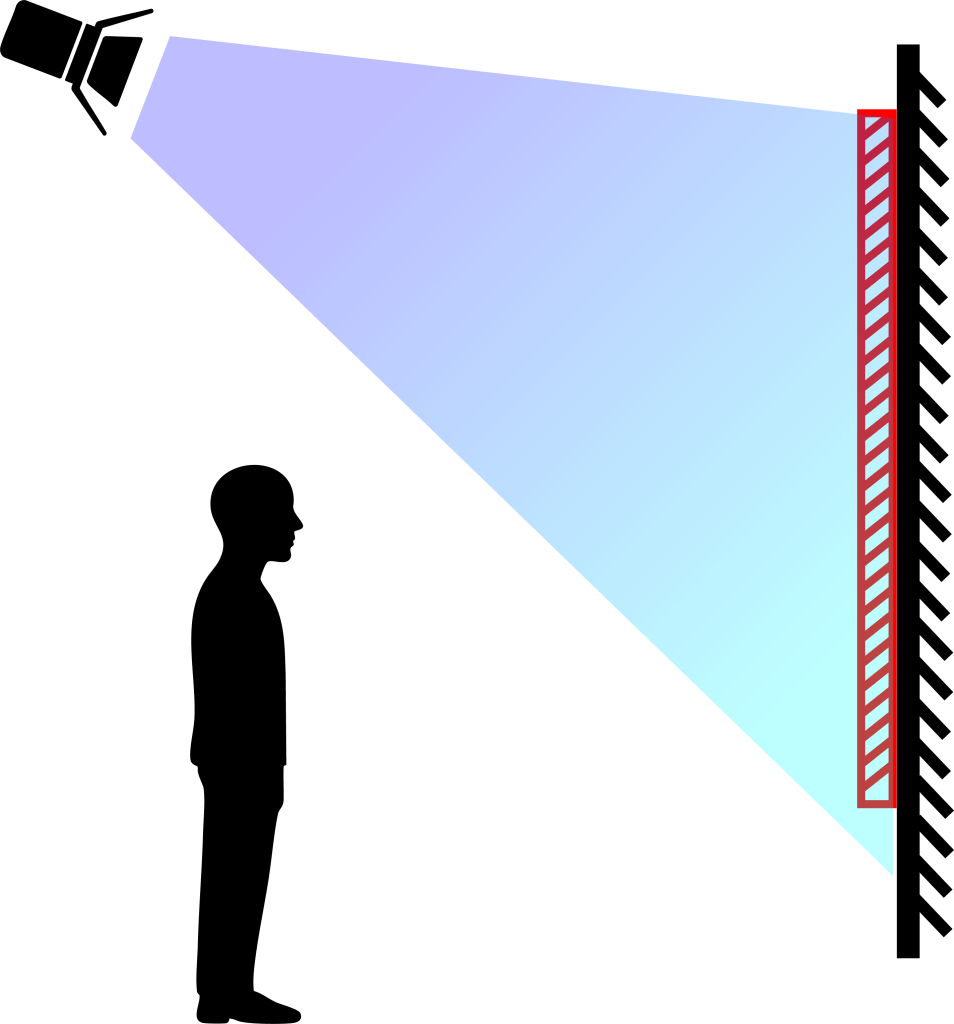

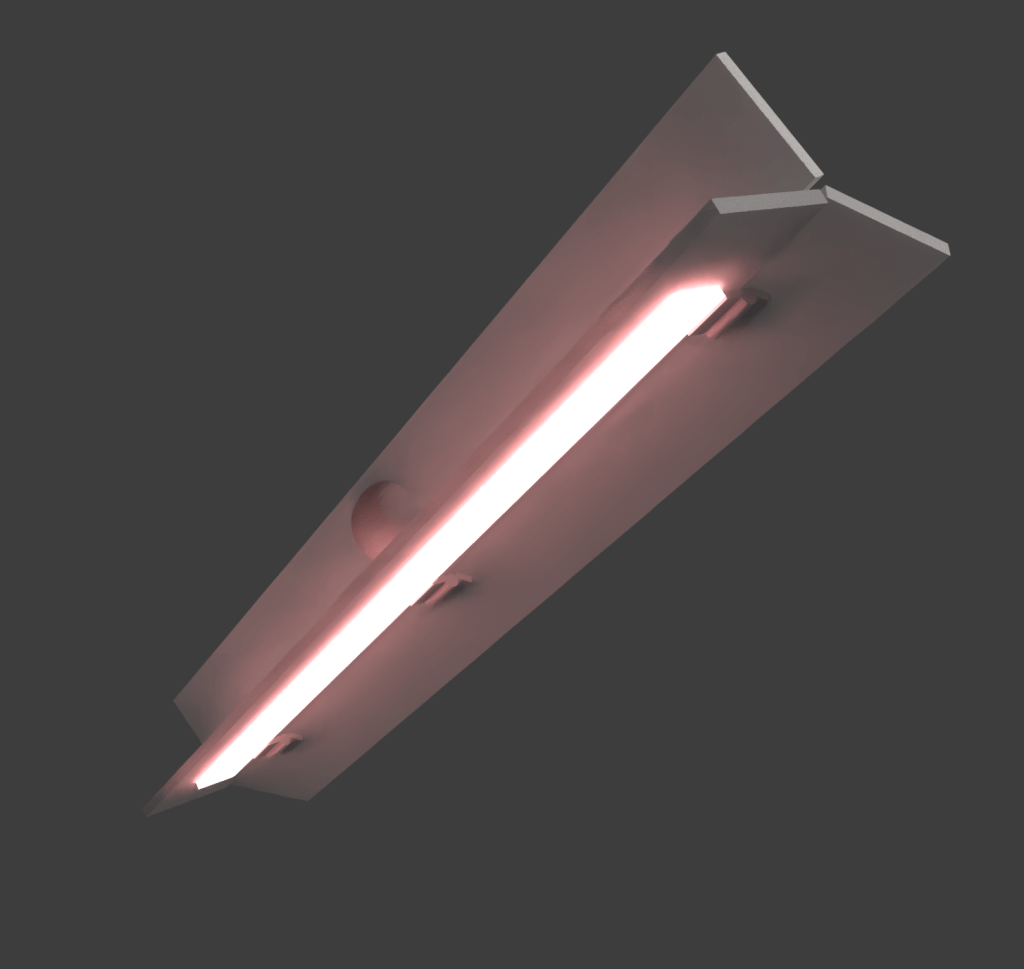

My initial idea was to simply project light onto the painting, positioning a projector above the canvas, much like a conventional projection onto a screen. However, this soon felt insufficient. The projector, as a prefabricated industrial product, resisted integration into the painterly logic of my work. It appeared as a foreign object—conceptually disconnected, as if forcefully attached rather than internally justified.

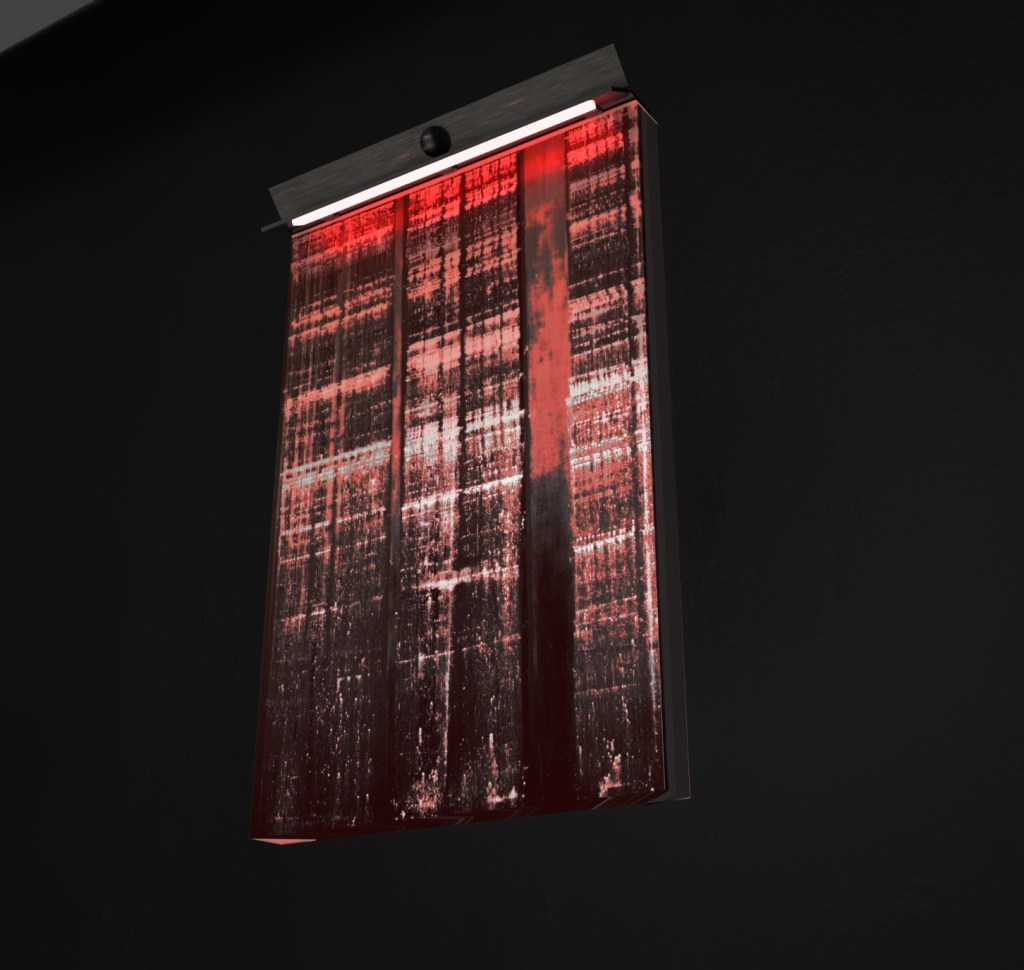

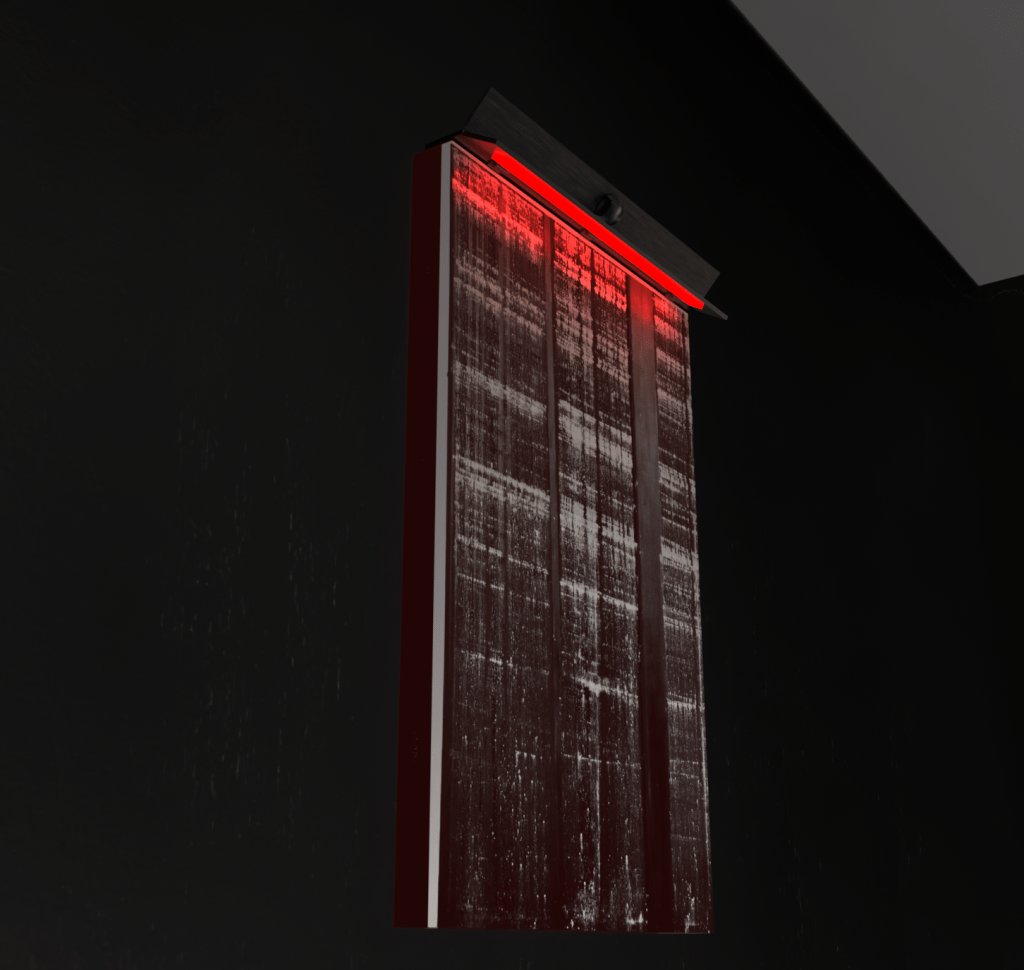

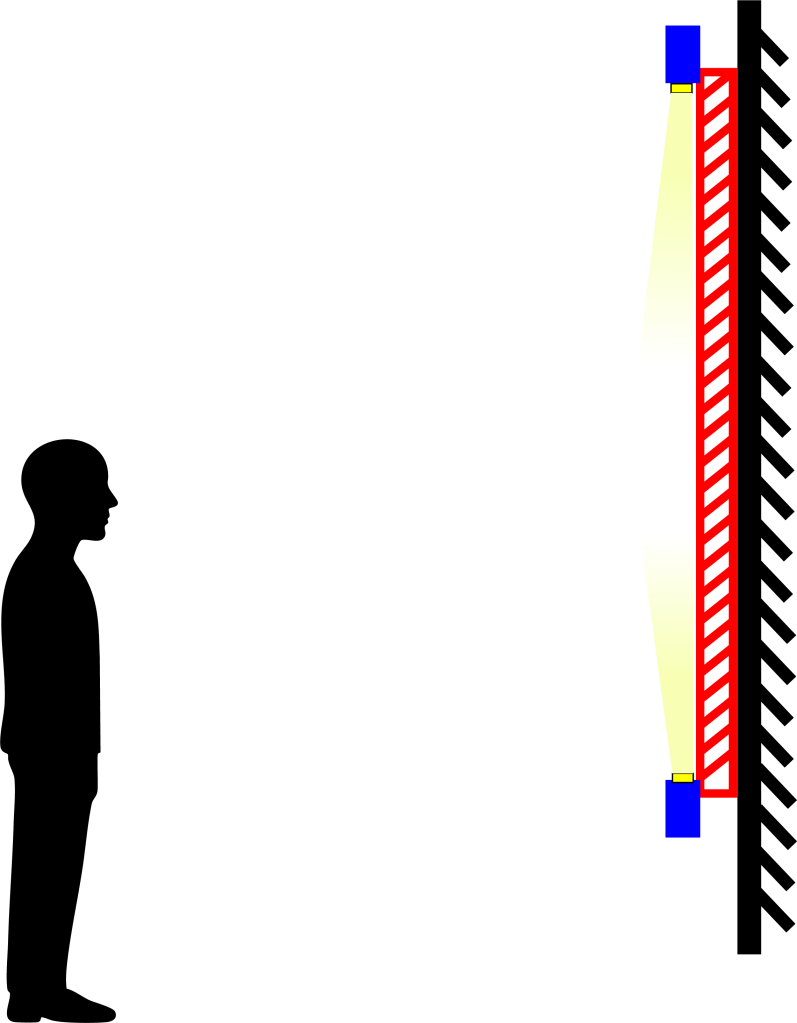

Consequently, I turned my attention back to the canvas itself, exploring how light could be embedded within or harmoniously integrated into the painting’s physical structure. This led to a second proposal, in which I designed a custom box painted in a matching colour to encase the light source—transforming it into a sealed, museum-like object. While this resolved the issue of visual coherence, it introduced a new limitation: the work became static and enclosed, losing the sense of openness and material immediacy that I was pursuing. A continuously illuminated light failed to evoke the act of “revelation” that was central to my practice.

To address this, I began designing an interactive lighting system that would respond to the viewer’s presence, creating an experience of interruption, surprise, or exposure. My plan was for the light to flicker irregularly whenever a viewer approached—mimicking the erratic pulse of a malfunctioning screen.

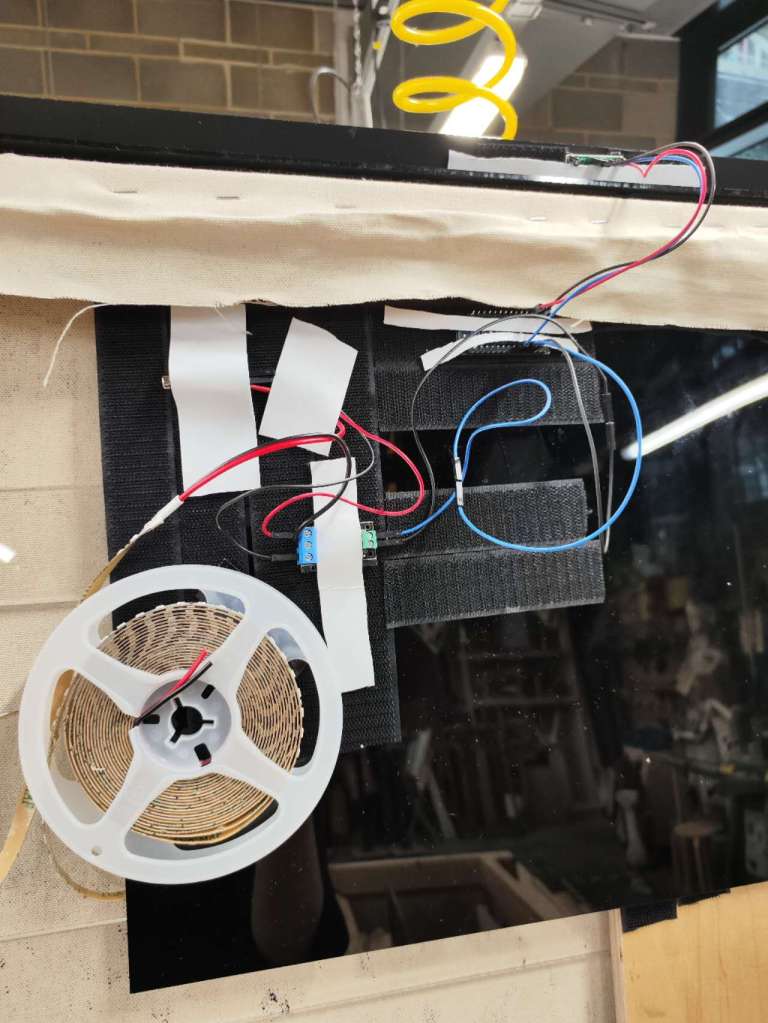

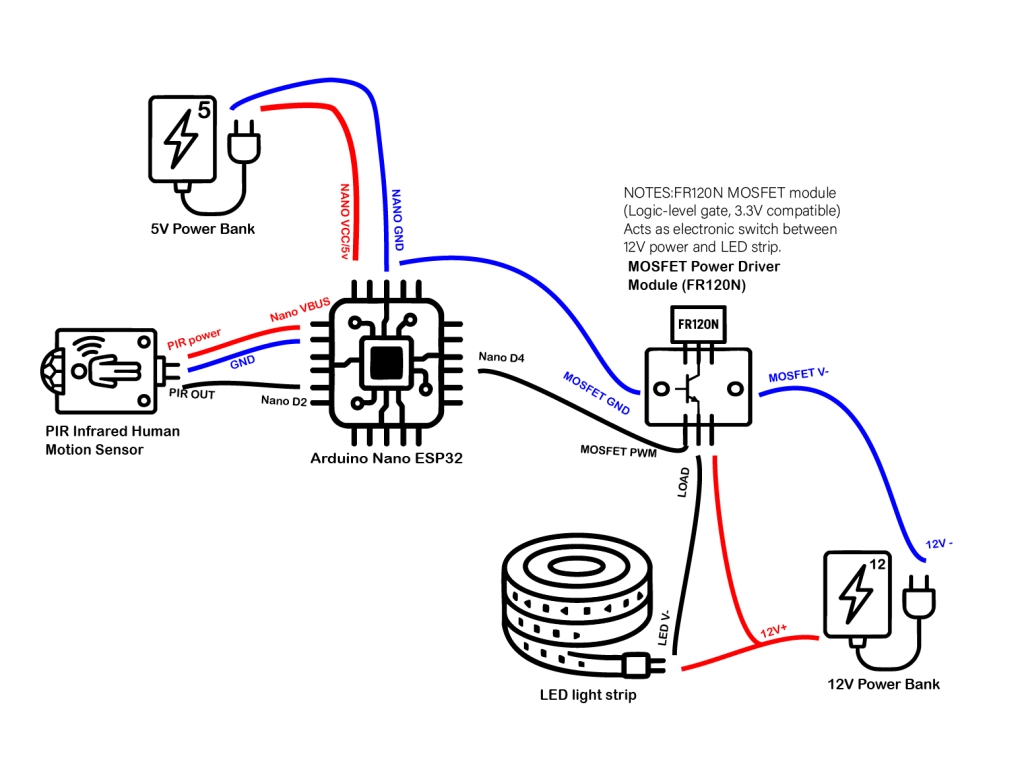

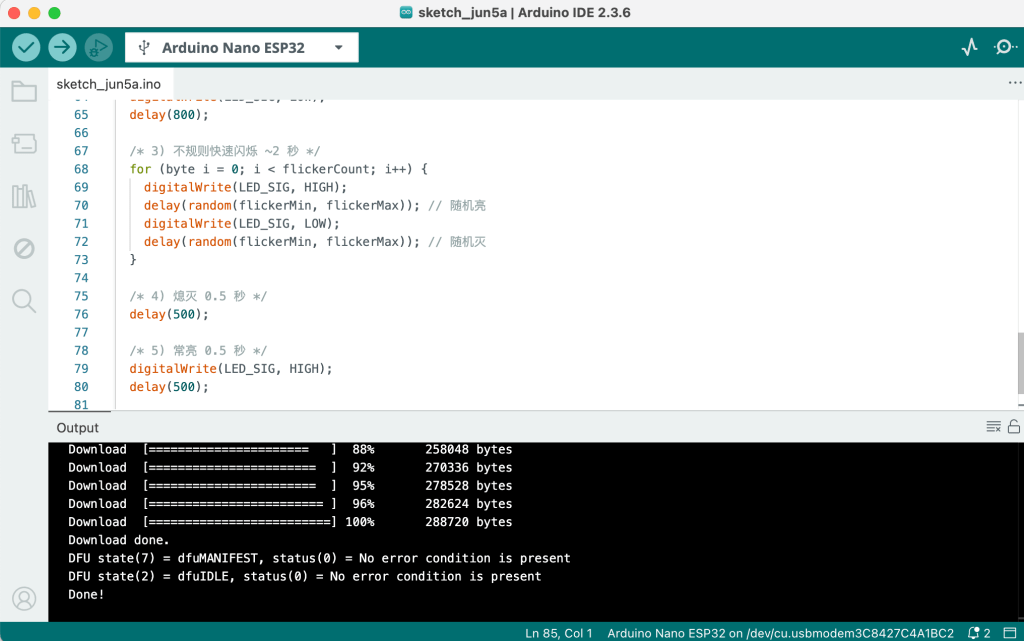

To achieve this, I developed a circuit using the following components:

- Arduino Nano ESP32 microcontroller (to run logic and control the flickering sequence),

- PIR motion sensor (to detect the viewer’s movement),

- MOSFET driver FR120N (to switch current and enable high-frequency flickering),

- LED strip (to project light onto the canvas),

- and various connectors, jump wires, adapters, and power supplies.

Starting from zero experience in electronics, I learned basic circuit design and programming to construct the system, which is documented in both the circuit diagram and the prototype photographs. The interactive mechanism functioned successfully—the light responded as intended—but the aesthetic outcome was unsatisfying. The LED produced only a superficial tint, like a digital filter overlaying the painting, rather than transforming it in a substantial way.

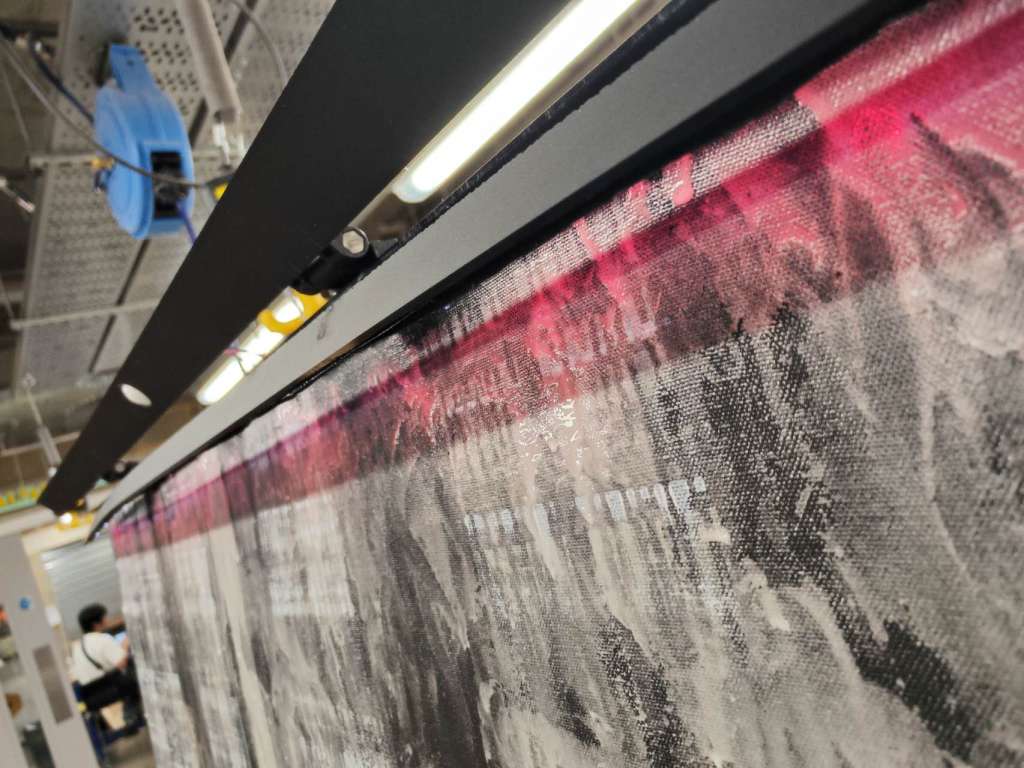

Further research led me to experiment with fluorescent pigments, materials that reveal completely different colours only when exposed to ultraviolet light. For instance, white or transparent pigments could suddenly glow red or green under a specific wavelength. I used STARGlow fluorescent pigments in combination with a 365 nm UV LED strip sourced from the United States. The UV light, almost invisible to the naked eye, activated hidden chromatic shifts on the canvas—an effect both subtle and uncanny.

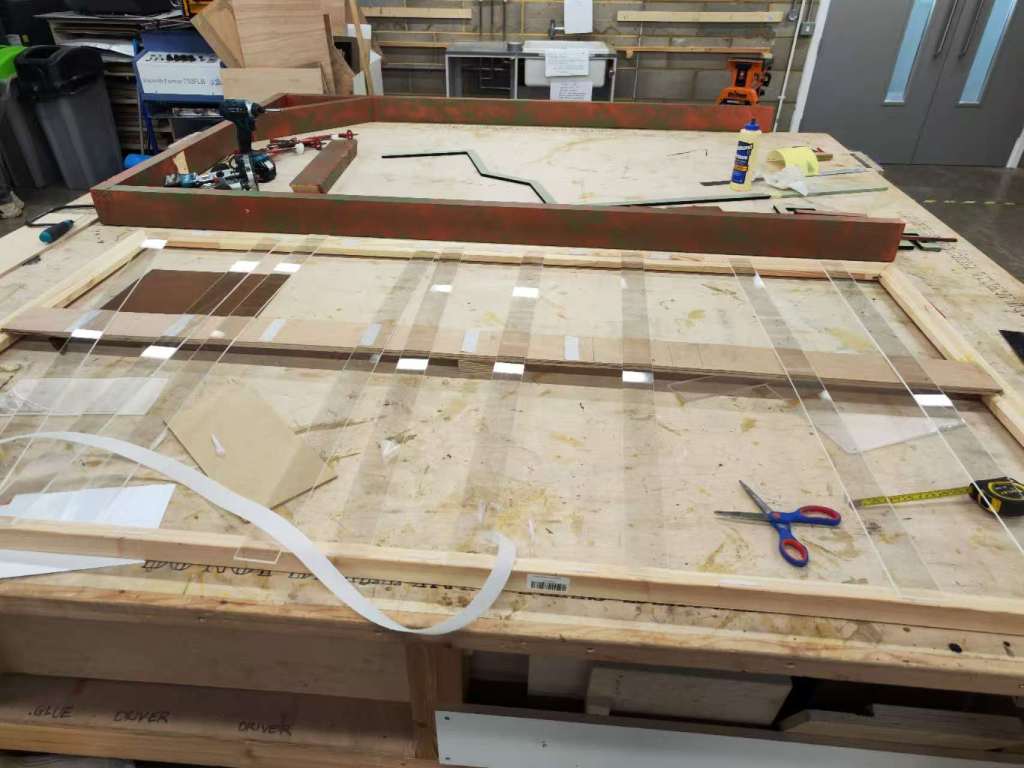

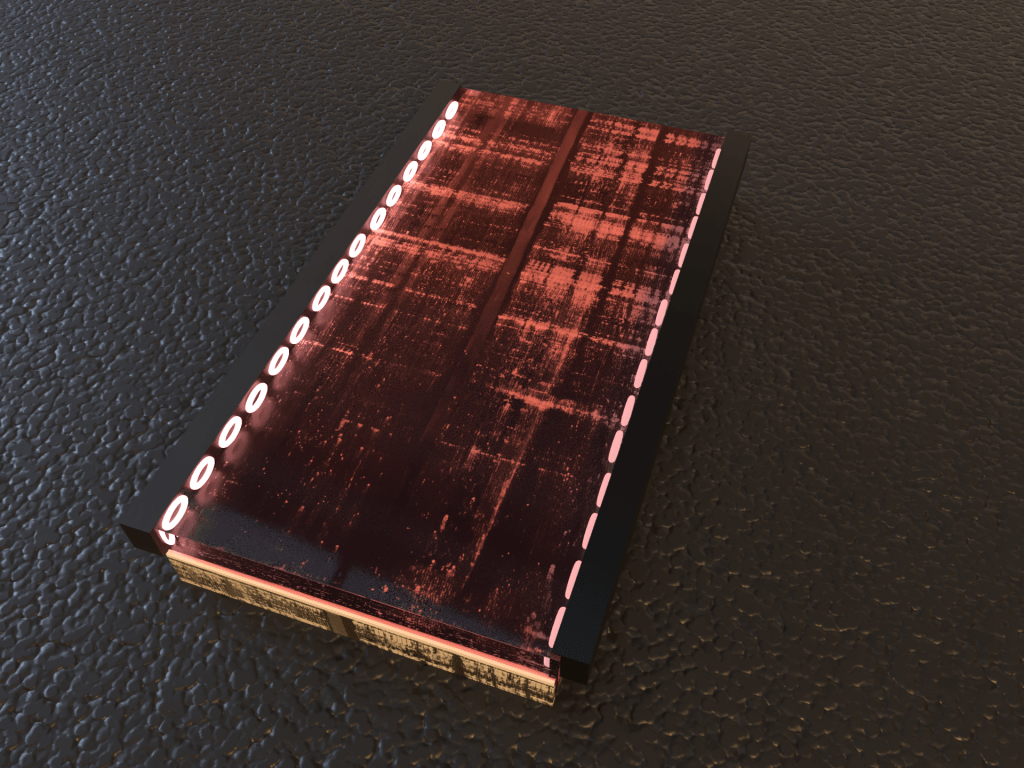

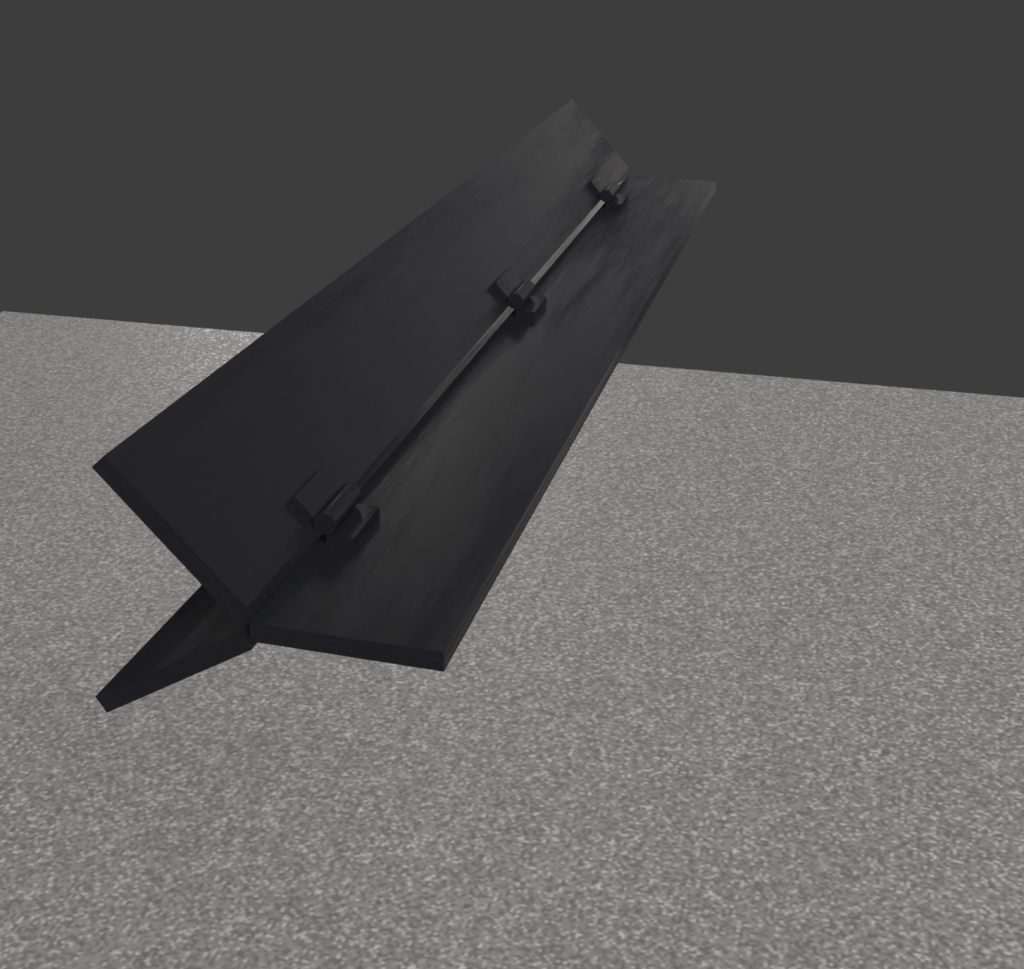

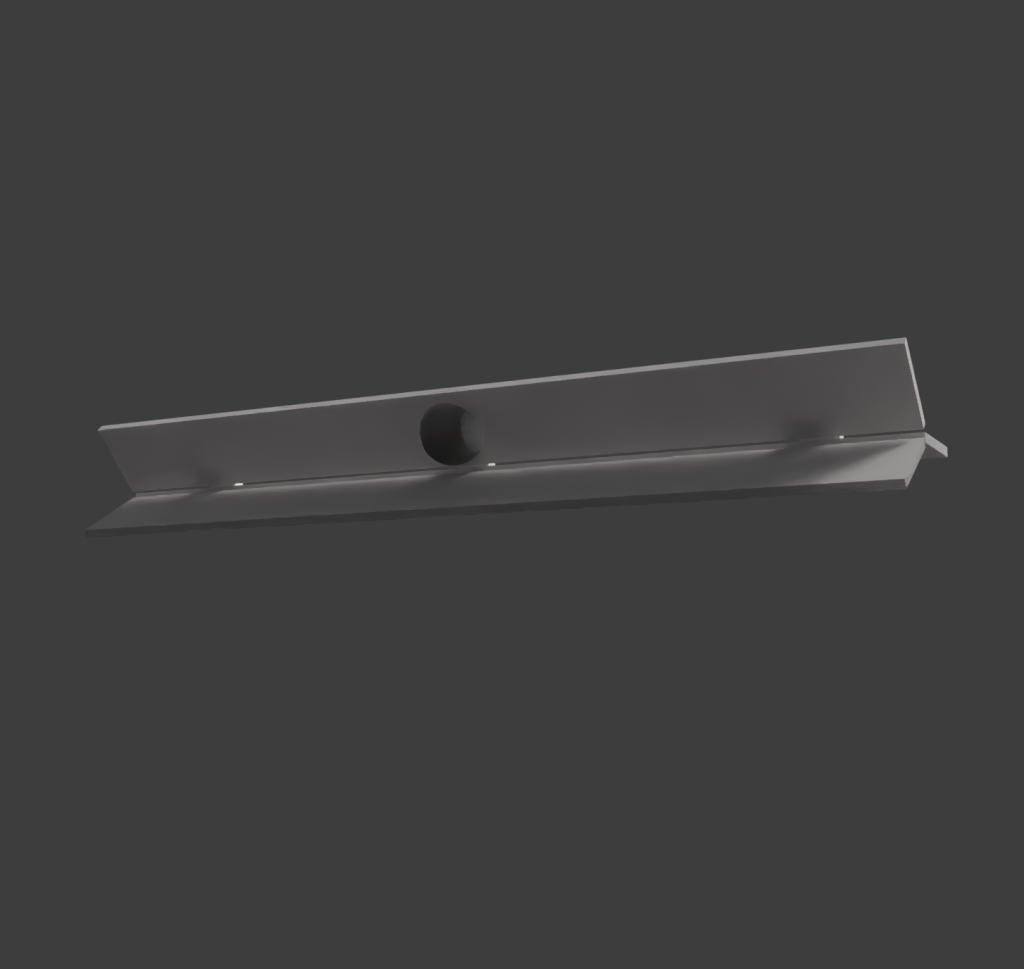

To house the lighting system, I designed a black structural casing with three hinged panels that could seamlessly attach to the canvas surface . The final 3D model visualised how the piece would appear in a darkened exhibition space.

Unfortunately, due to the limited power of the 12 V UV strip, the light could not cover the full 180 cm width of the canvas—only a small portion was effectively activated. As a result, for the final MA Show, I exhibited the painting alone without the interactive light component. Nevertheless, the experiment provided a valuable learning experience. Through this process, my inquiry shifted from what to paint toward what constitutes a painting—from surface representation to the material and technological conditions that allow painting to exist.

Process Documentation

MA SHOW Documentation

Resovled Works

Painting in the Age of Acceleration

In this paper, I continue the structure and approach of the previous chapter, Artistic Practice: beginning with a general overview that traces how my thoughts and research have gradually unfolded; followed by a discussion of my subsequent inquiry into literature and case studies—particularly Marcus Gilroy-Ware’s Filling the Void: Emotion, Capitalism and Social Media, whose analysis of contemporary social media resonates deeply with my own artistic and theoretical investigations.

At first, I had no clear research direction—I neither knew what I wanted to do nor what truly concerned me. So I turned inward, revisiting my BA graduation project [Reading More…]: why did I create in that way? Why was I drawn to the theme of the “sublime,” especially the traditional notions of the natural and the psychological sublime? Building upon that, I began to trace the genealogy of the sublime—from the traditional to the postmodern and, eventually, the technological sublime—using Jean-François Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition as a conceptual entry point. Gradually, a clearer answer emerged. From Kant’s rational sublime to Burke’s sublime of terror and distance, and finally to Barnett Newman’s declaration that “the sublime is now,” the subject of the sublime shifted from an external nature to the inner field of human perception and experience.

Looking back at my BA period, I pursued a form of bodily and improvisational expression, attempting to create within the painting a linguistic vacuum—a space of meaninglessness that forces the viewer to pause. This momentary suspension of meaning resonated with Newman’s notion of the sublime as immediacy in Vir Heroicus Sublimis, and Lyotard’s idea of “presenting the unpresentable.(Lyotard, 1982).” Yet at that time, I still could not articulate why I painted—it felt as though I were merely finding a place to anchor what I had already done. I began to realize that mere formal or sensory intensity was no longer sufficient to address the fundamental question of making.

Thus I turned toward existential philosophy. In a time when ultimate answers have collapsed, meaning has become void, and both reason and logic have been uprooted, existentialism attempts to construct a humanist path—taking the absurd as its fundamental condition, and viewing the pursuit of personal meaning as an act of resistance against it. In Camus’s sense, the absurd is not simple meaninglessness but the tension between humanity’s longing for meaning and the silence of the world (Camus, 1942). This helped me locate my reason for painting and explained why I had been drawn to the sublime. Hence, in my first Critical Reflection, I wrote that my art is not a philosophical conclusion or illustration, but rather an unfolding of existence. It faces the absurd moment while echoing Newman and Lyotard’s “unpresentable.” In other words, I see “myself” within painting—not as a concrete image or portrait, but as the unspeakable part of me that unfolds in the here and now, a convergence of self, place, and meaning.

I then began to reflect: why are my paintings always tense, heavy? Why do I constantly seek to evoke intensity, anxiety, unease? As I shifted my gaze from the self to the world, I gradually realized that such tension and unease were not purely inner emotions but the externalized pressure of social speed and technological acceleration. I stepped out of introspection and began to examine my surroundings more closely—those seemingly “mundane everyday” phenomena I had long taken for granted.

In my further research, Paul Virilio’s philosophy of speed (1991) and Hartmut Rosa’s theory of social acceleration (2013) deeply influenced me. They unveiled the structural logic behind the “everyday,” making me aware that my inner anxiety and restlessness stemmed from a subtle, involuntary pull—a society that cannot stop, that must continuously upgrade itself. As Rosa writes in Social Acceleration, this “game of escalation” is sustained not by the desire for more, but by the fear of less. We feel perpetually insufficient not because we are greedy, but because we are caught on an endlessly descending escalator—even if you stand still, you are carried downward. Any attempt to pause results in displacement, for competition is omnipresent; there is no longer a stable platform on which one might rest or declare “enough”(Rosa, 2020, p. 9). If Virilio exposes how technology dissolves space and perception through speed, Rosa reveals how acceleration has become a cultural constant embedded in the very structure of modernity.

If capitalism’s expansion resembles a perpetual “temple run”—where halting growth means being devoured by debt or overtaken by rivals—then individuals within it are inevitably swept up by this necessity of progress. In other words, the system requires continual economic growth, technological acceleration, and cultural innovation merely to maintain itself. Acceleration becomes the means of stability—and stability, therefore, can never truly be achieved (Rosa, 2020). This led me to realize that the tense, restless quality in my paintings might itself be a bodily response to the condition of an accelerated society.

“If it still works, it’s already obsolete.” — this was Lord Mountbatten’s motto while overseeing Britain’s weapons development during World War II. Initially, the phrase described the logic of wartime competition: once a weapon could still function, it could no longer surprise the enemy—and therefore lost its effectiveness. Ironically, this logic did not vanish with the end of war; it was transplanted into consumer culture. What was once the race to build faster weapons has become the endless iteration of consumer products: as soon as a new item hits the market, it is instantly copied, updated, and replaced. Companies are compelled to launch the next “innovation cycle” to sustain this perpetual self-revolution. The targets struck are no longer enemies, but consumers—and culture itself. We all press the accelerator, chasing that advertised promise of the future: “You deserve better.” Yet this “better” exists only as a mirage deferred into the future. “Innovation” becomes an unquestionable faith, a moral obligation institutionalised as progress.

The relationship between human and world has shifted from romance and wonder to prediction and control. We no longer ask what the world or the people around us are saying, but what they can deliver, whether they can fulfil their promises (Rosa, 2020). Human relations grow distant and instrumental; empathy gives way to a cold rationality. Individuals are driven by speed and competition onto isolated tracks—each busy maintaining their own progress bar, concerned only with how to become “better,” with little energy left to care for others. Morality ceases to be an inner conviction and becomes a by-product of efficiency. This atomised social structure severs genuine connection between self, others, and the world, embodying the neoliberal illusion that every “independent individual” is free, while in fact each is privately bound to the machinery of acceleration.

In principle, such rupture and alienation should have provoked far greater social unrest—though fragments of it appear in news and everyday experience, they are never strong enough to transform the system. There must be a force that silently, almost elegantly, fills the void. It persuades us that everything can either be fixed or is already under control. That force is the development of technology itself. It masks the mechanisms of its own crisis production beneath the promise of “solution,” becoming a new kind of psychological sedative—a systemic “technology of happiness.”

In my mid-term research, I conceptualised this phenomenon as “Technological Re-enchantment.” Modern technology, on the surface, disenchants the world—banishing mystery through reason and efficiency—but in fact, through “human-centred interfaces,” “frictionless experiences,” and “happiness algorithms,” it re-clothes reason with a new mysticism, constructing an alternative belief system. People are enveloped in an illusion of efficiency and pleasure, deriving a sense of mastery from the smoothness of operation, while unconsciously being shaped by its logic (De, 2025). Technology thus ceases to be a mere tool and becomes an ideological apparatus: it disguises seamless operation as freedom itself, and translates automated convenience into the illusion of happiness.

This argument later found confirmation in my reading of Marcus Gilroy-Ware’s Filling the Void: Emotion, Capitalism and Social Media (2017). Gilroy-Ware reveals how digital social media, using emotion as currency and algorithms as its theology, governs the user’s attention and affect. He shows that social media is not simply a medium of communication but an engine of “emotional capitalism,” transforming feeling into data and attention into labour through continuous loops of stimulation and feedback. This led my research to focus on a more defined question: how technology, within a post-capitalist context, reshapes human cognition—not only altering how we see the world, but how we come to become ourselves.

In my research, I extended Marshall McLuhan’s concept of “the medium is the message” and proposed a perspective I call “the medium/technology as cognition.” In other words, the medium is not a neutral tool but an environment that shapes cognition and behaviour. Digital media, through its algorithms and interface structures, directly influences how we perceive the world and how our thought processes unfold. From this perspective, technology is no longer an external force but a constitutive logic embedded in the fabric of everyday life.

To illustrate this, I often refer to the case of food-delivery riders. These platforms use algorithms to regulate every beat of the riders’ labour rhythm: to avoid penalties, they must risk their safety by compressing each delivery into shorter intervals. On the other side of the interface, the consumer sees only a moving blue dot, an estimated arrival time, and the occasional pop-up coupon. This is what I call “interface ideology”: the interface’s smoothness and visual clarity conceal structural violence beneath the surface. The algorithmic system masks human cost under the guise of “efficiency,” translating the pain of labour into data, then aestheticising it into a “seamless user experience.” The interface thus functions as both a veil and a sedative—it makes violence appear cute.

Beyond that, technology continues to commodify time itself: time is sliced, quantified, and even collateralised. Individuals, tethered by algorithms and devices, are drawn into a perpetual “chronometric economy.” Within this mechanism, the present loses its thickness; it becomes a distributable resource, a unit of production. People are trained to maximise temporal efficiency rather than to inhabit time. As a result, time is no longer an existential experience but a resource to be traded and extracted.

In the field of art, many artists have sought to resist this logic in their own ways. Christian Marclay’s The Clock forces the viewer to synchronise themselves with a 24-hour loop, exposing the modern subject’s captivity within the temporal system. Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980–1981 transforms the body into a cog in an industrial time machine—punching a clock every hour, taking a photo, repeating the act for an entire year. Both works reveal that once humans lose control over time, the body itself becomes the unit of measurement. In this sense, their works are not only records of time but also acts against time—extreme repetitions that expose the very structure of temporality.

At the same time, I am inspired by digital artist Rosa Menkman’s Glitch Aesthetics (2011). She does not treat technological malfunction as mere error but as a form of “Constructive Glitch.” Within a logic of “frictionless experience,” the user’s agency is replaced by automated processes, and the glitch becomes the critical moment that ruptures this illusion. It is like suddenly realising, within a dream, that one is dreaming—that instant of lucidity exposes both the boundaries of the system and our passive position within it.

Consequently, “revelation” has become the methodological core of my artistic practice—a principle I elaborated on in the previous chapter, Artistic Practice. Revelation means making invisible systems visible again, reintroducing “friction” into the field of perception. Through repetition and deviation in painting, I seek to re-materialise what has been flattened by the digital. My work does not directly simulate the visual effects of glitches; rather, through the physical delay of labour and the resistance of material, it allows viewers to feel that suppressed sense of friction. This friction emerges both from the tactile resistance between pigment and canvas and from the temporal lag between my bodily motion and the logic of the digital system.

Within this complex theoretical constellation, I seem to have grasped a crucial thread: as technology builds a world that is convenient, accessible, and frictionless, it simultaneously reshapes our cognitive patterns and structures of desire. It disguises speed and smoothness as freedom, and algorithms as neutrality. This insight was further reinforced when I read Gilroy-Ware’s Filling the Void. His discussion of “emotional automation” made me realise that technology’s shaping of perception and desire parallels my own exploration of material resistance and loss of control in painting—two expressions of the same condition, one operating inside the digital system, the other surfacing through the material body of paint (Gilroy-Ware, 2017, p. 46).

It is precisely at this point that my research begins to resonate with Gilroy-Ware’s ideas. Technology has built for us a world that appears convenient, fast, and accessible—a space of frictionless experience. Yet the smoother the experience, the more it deserves to be questioned. Does convenience and accessibility necessarily mean “better”?

Here, I want to recall a quote by Aral Balkan: “There are only two industries that refer to their customers as ‘users’—one is drug dealers, and the other is software developers.” The remark sounds humorous at first, but it exposes the dangerously intimate relationship between humans and technology. Addiction, in the case of drugs, is often semi-compulsive: it consumes both body and mind. Social media, video platforms, and utility apps function in much the same way—they trap us in unconscious repetition under the guise of “convenience, efficiency, and accessibility.” These systems are designed to make scrolling endless, so that one can never truly reach the end. We exhaust our time and attention in constant browsing and refreshing, suffer anxiety from information overload, and yet remain enclosed within the “illusion of connectedness” fabricated by social networks.

When a system is always awake, always responsive, and constantly seeking to automate our behaviour, we easily lose both judgment and agency without even noticing. In such a condition, it becomes impossible to tell whether the next notification is information, bait, or dosage. Addiction, then, is no longer a physiological reaction but a social norm—a codified form of emotional management. The incidents spawned by digital media—rumours, online violence, attention addiction, academic burnout—reveal how pervasive this mechanism has become. In other words, we must remain cautious of things that are “immediately accessible,” even when they appear intuitive, friendly, or harmless by design.

As I discussed earlier, the accelerated society forces individuals to look only forward, to measure the world through quantifiable and assessable standards. Everything is purified and smoothed in the name of “efficiency.” Consequently, our relationship with the world grows silent, and our relationships with others become atomised. Logically, such a social structure should have produced massive crises—but what we see instead is a strange soft landing, as if everything were cushioned by a layer of gentle light. Pain persists, but it is wrapped in a soft-focus filter.

This is precisely what Gilroy-Ware describes as the mechanism of “filling the void.” Technology transforms our emotions, desires, and anxieties into consumable products, using attention as raw material. It temporarily anaesthetises systemic unhappiness through what might be called emotional capitalism (2017, p. 106). In other words, technology constructs a digital pleasure apparatus that blurs the boundary between wanting and liking, between anticipation and satisfaction. This confusion is not merely psychological—it is the core strategy of capital itself: to keep desire perpetually hungry and fulfillment perpetually deferred to the next click.

Social media, virtual reality, and short-form video platforms never truly deliver satisfaction; instead, they manufacture expectation. This “pleasure of anticipation” is their true commodity. Algorithms prolong attention by delaying gratification, maximising the temporal profit of capital. As the feed amplifies the impulse to “want,” any image that carries a promise of pleasure—food, sex, friendship, pets—draws us into endless repetition, even though it never truly satisfies. As psychologist Barry Schwartz (2005) notes, “What is connected to dopamine is not having, but wanting itself—the excitement and arousal of anticipation.”

Thus, the mere presence of images representing what we want—those curated by Instagram, Facebook, or Pinterest—is enough to make us feel we “almost have it.” Viewing a photograph of food makes us feel we are “about to taste it”; seeing pictures of friends makes us feel we are “about to meet them”; watching a cat video makes us feel we are “about to touch it.” This pleasure driven by anticipation defines the inner logic of timeline consumption: what truly delights us is not the image itself, but the illusion it produces—the sense that what we see is “about to become ours.” At its core lies a temporal structure: the creation of an eternal “almost-now”—a present that never arrives, yet is always coming (Gilroy-Ware, 2017, p. 56).

When we put down our phones and our nerves withdraw from this illusion of wanting, the void reappears—anxiety, loneliness, and meaninglessness resurface, and the Void once again calls us back into its arms, perpetuating the cycle. In other words, the tragedies induced by social media are not caused by the tools themselves, but by the larger social architecture that sustains them. Social media exists to maintain that structure. We are not enslaved by individual products, but by the world logic that operates through them.

It could be said that capitalism has evolved from a system that was once “functionally productive” into one that no longer produces meaning but manufactures emotional disturbance—from a capitalism that could exist without social media, to one that depends on it for survival. Gilroy-Ware’s analysis of “anticipatory pleasure” perfectly echoes my earlier reflections on new media: the photographs and information stored on a hard drive are never truly “there”—they are nothing but spaceless, timeless constellations of data. When we gaze at these images on a screen, it feels as if we are returning to the past; yet this illusion of return is itself the product of technology—a simulation of a “controllable present.”

This resonates deeply with my own artistic exploration: my insistence on materiality and the tangible presence of being. If digital media continually erases the reality of time and the body, then the meaning of painting, for me, is to reclaim, within this evacuated speed, a form through which existence can once again be touched.

In the end, I must admit that painting—or indeed any act that does not aim to subvert existing structures—cannot resolve the problem at its root. The act of painting, to me, resembles the existential confrontation with the absurd: a condition of being thrown into the world, of facing it without choice—a choice of no choice. And I am aware that for many people who face the weight of daily tasks and the exhaustion of ordinary life, the search for meaning itself can feel like a burden. For them, the illusions that technology provides may serve as a necessary supplement, a small dose of encouragement to keep moving forward.

As Gilroy-Ware writes in the final chapter of Filling the Void, the ultimate cause lies in capitalism. Yet here, capital is no longer an economic option or an abstract concept—it is not singular, static, or fixed. Capitalist culture is fluid, mutating, constantly reorganising itself. In our time, we seem unable to envision an alternative system. As capitalist realism suggests, this appears to be the only reality left to us.

References

Camus, A. (1942). The Myth of Sisyphus. Éditions Gallimard.

Gilroy-Ware, M. (2017) Filling the Void: Emotion, Capitalism and Social Media. London: Repeater Books.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1982). PRESENTING THE UNPRESENTABLE: THE SUBLIME. [online] Artforum. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/features/presenting-the-unpresentable-the-sublime-208373/.

Marclay, C. (2010) The Clock . London: White Cube.

Menkman, R. (2011) The Glitch Moment(um). Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

Newman, B., & Strick, J. (1994). The sublime is now: the early work of Barnett Newman; paintings and drawings 1944-1949. New York: Pace/Wildenstein.

Rosa, H. (2013) Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rosa, H. (2020) The Uncontrollability of the World. Cambridge: Polity.

Virilio, P. (1991). The Aesthetics of Disappearance. Semiotext(e).