Preface (Artist Statement)

This paper revisits and systematises the recent shifts in my theoretical research, observations and artistic practice. Whereas the previous phase was devoted to philosophical and existential reflection, the current stage concentrates on the social constellation of speed and efficiency and the ways in which technology amplifies their impact on human life. My thinking is informed by Paul Virilio’s philosophy of speed, or dromology (Virilio, 1997), Hartmut Rosa’s theory of social acceleration (Rosa, 2013) and Lev Manovich’s definition of new media (Manovich, 2001). I study how digital media and devices reshape cognition and everyday routines, and my painting—within this framework—functions as a kind of performative act: the work no longer seeks figurative depiction but serves instead as a record of process. Casting myself as an “information printer,” I use pre‑fabricated, modular brushes to repeatedly produce encoded marks on a black canvas; the mechanical friction and repetition of my arm ultimately yield an image that recalls the snow‑storm static of an old CRT television.

Since the Enlightenment, rationalism and scientific method have “dis‑enchanted” the world: nature has shed its mystical veil, phenomena have been quantified and predicted, and machines have gradually replaced human labour. Yet the digital age stages a new form of technological re‑enchantment. Flashy interface animations, “humanized” interaction design and 24/7 information streams offer a friction‑free experience while quietly erecting a belief system that disciplines perception and behaviour. Smartphones, autonomous vehicles and user‑centred software are packaged as harmless companions; more pervasive than any mediaeval miracle, this enchantment—invoking happiness and efficiency—flattens everything into computable, predictable logic. Ostensibly a human‑centred apparatus (Foucault, 1977), it silently erodes personal agency and immerses users in an endless ‘happiness‑experience machine.’

Medium as Cognition

If a contemporary life were likened to a painting, the traditional work would pass through a long, material itinerary: the painter spends days or years layering pigment; the piece is then framed and hung—an equivalent to a graduation ceremony—before a curator meticulously arranges lighting, sight‑lines and theme. Finally, viewers must approach, step back, circle around and concentrate in order to read it. Meaning is sustained by spatial distance and temporal delay.

The digital age rewrites that route entirely. Screens flatten distance and compress time: a painting can be executed wholly in virtual space, software simulating every stroke; even when born in the studio, a scanner translates its heavy pigments into strings of colour values and coordinates. To the viewer it becomes a near‑weightless image drifting through the data torrent; if it fails to catch the eye in that first fraction of a second, it is whisked away. What was meant to reduce communication cost now enfolds us into the cost. As Virilio remarks, “You don’t have speed; you are speed” (Virilio, 1995). On social media each person is compressed into units, tags and latent commercial value. In other words, while we accelerate access to information, we ourselves are converted by others.

This conversion fosters fast‑food content, short‑form video and image‑centric feeds. The first removes resistance to intake, the second abbreviates decision‑time, the third raises transmission efficiency by replacing deep thought with at‑a‑glance legibility. Critiquing “fake news” or fragmentation alone merely swaps one surface phenomenon for another. The crucial point is that a medium is not a neutral technological prosthesis but a cognitive environment that co‑forms subject and object. Hence the questions that guide me: What is new media? How is it constituted? How does it differ from traditional, physical media? And how does that difference flow back to reorganise reality?

Lev Manovich puts it succinctly: “All new‑media objects, whether created from scratch on computers or converted from analogue sources, are composed of digital code—they are numerical representations” (Manovich, 2001, p. 52). Two operations are implied: digitization, which discretizes the continuous and uncertain into measurable data, and algorithmic manipulation, which lets that data be copied, edited and recombined without limit. Digital objects thereby gain a Platonic, abstract ‘eternity’, ready to be frozen or duplicated across domains. Yet the tragedy is that what Plato filed under reason we now consign wholesale to an algorithmic factory: algorithm becomes reason, efficiency becomes telos. Technical rationality pursues ever faster, more accurate and more controllable management of information—standardising formats and protocols so as to enable mass replication and automation. If we still regard technology as a detachable, side‑effect‑free prosthesis, we fool ourselves into believing we command a productivity utopia; reality is otherwise—the medium actively shapes perception, emotion and conduct. Whose efficiency, then, and whose profit? Are we factory owners or data points?

A vivid case is the investigative article ‘Delivery Riders, Trapped in the System’ (Renwu Magazine, 2020). Interviews with couriers reveal that Meituan cut the delivery window for a 3‑km order from 60 to 38 minutes between 2016 and 2019. To avoid penalties, riders speed, run red lights and crash; accidents become mere coefficients in the profit model. For the user, the interface shows only a moving dot and an ETA, attention swiftly hijacked by coupons and rating pop‑ups. The medium filters and conceals the algorithmic cost, leaving the user unaware. New media, therefore, is not just images or clips on a screen but a data‑algorithm apparatus that stores, produces and orchestrates information—an apparatus in Foucault’s sense (Foucault, 1977). While we luxuriate in seamless UX, the medium has already become the precondition of cognition, the scaffold of action and an invisible regime of discipline, making the world appear more humane even as it silently reshapes us.

Medium as Time

When technology drives speed to its outer limits, time turns into a resource more precious than gold. As Hartmut Rosa notes in Social Acceleration (Rosa, 2013, pp. 100‑101), modern technologies transform the traditional linear sense of time into an abstract, divisible and quantifiable chronometric time. Like battery charge, it is sliced, priced and sold—stripped of continuity and fully commodified. Smart devices become its chief accomplices: precise timers and “helpful” planners convert every second into value, while relentless notifications whisper, “You are not alone—something more exciting is happening elsewhere.” Pop‑up adverts add another refrain: “Your time deserves a better experience!” Paul Virilio had already warned, in “The Overexposed City”, that once screens pervade everyday life, the distinction between here and there collapses (Virilio, 1986).

For digital platforms, our attention and time are batteries to be drained—unused capacity is wasted capacity. Gradually a new temporal consciousness takes hold: my time must be valuable, my future must surpass the present. Idling feels sinful, for each unspent minute “self‑discharges.” If new media is the candy coating that builds a gorgeous society of spectacle, then the operational logic of modern society is the shell concealed beneath, ready to explode at anyone who dares to stop. Rosa puts it starkly: “In terms of cultural perception, this escalatory perspective has gradually turned from a promise into a threat.”(Rosa, 2020, p. 9).

Failure to remain faster, better, more efficient risks job loss, business closure and shrinking welfare; political legitimacy itself erodes. We stand on a down‑escalator: only by running upward do we maintain altitude; to climb higher we must outpace the descent, and once we pause we are hurled downward. Rest, hesitation and reflection are recast as moral failings.

To secure even present time is not enough; the future must also be collateralised. Credit scores, loans, bonds and insurance—all in the name of greater happiness—bind each seeker of well‑being. These so‑called investments are, in fact, the sale of future time: once the contract is inked, the switch clicks—tick‑tock, tick‑tock—the meter starts. The signatory dashes like a courier riding against traffic: no longer flesh and blood, but a datum in a bank ledger. The very instruments criticised for control and efficiency become the tools of survival. The only solace, perhaps, is the shimmering tomorrow eternally promised by new media.

Medium as Matter

Philosophers, sociologists and artists all attempt—by their own paths—to ease the overload of information in contemporary life. Paul Virilio, in Grey Ecology, regards speed as a form of pollution; his politics of deceleration seeks to alert the public and to re‑calibrate and slow technological acceleration (Virilio, 2009). Within his dromology, the Integral Accident functions as a perpetual alarm: every increment of velocity heightens the magnitude of disaster; once speed slips out of control, a ‘speed story’ becomes a ‘speed accident’—car crashes, air disasters, derailments, online mobbing, fake news and mass anxiety share the same genealogy (Virilio, 1995).

Hartmut Rosa likewise advocates slowing down. His concept of Temporal Sovereignty urges individuals and institutions to reclaim the allocation of rhythm, carving spaces for pause, slowness and reflection (Rosa, 2013). He later proposes Resonance, which echoes with Virilio’s accident: relentless quests for control breed greater uncontrollability, while excessive mastery dulls our capacity to resonate with the world. Rosa calls for relations that are affectedness, response, adaptive transformation, uncontrollability rather than possessive, so that the world can speak instead of being flattened by acceleration (Rosa, 2020).

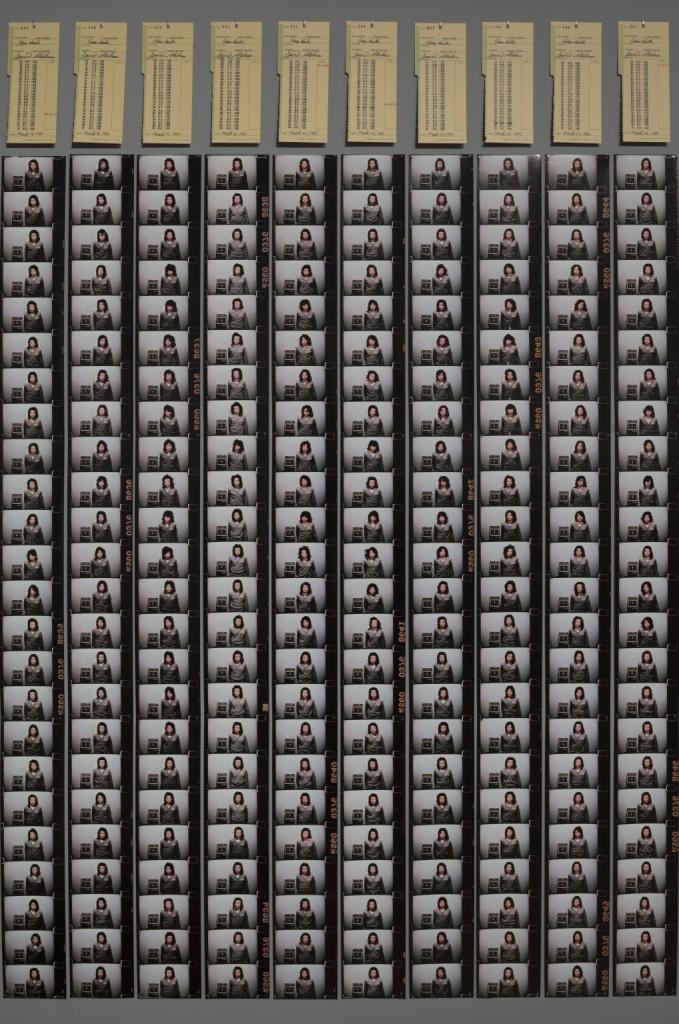

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1980-1981,1980–1,

Artists address the same problem through sensory strategies. Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980–1981demanded an hourly time‑clock punch and photograph for 365 days, yielding 8 760 cards and images. The work forcibly aligns life‑time with art‑time, pressing the body into industrial cadence and, via grid display, visualising sliced moments as a continuous timeline (Hsieh, 1981).

Christian Marclay’s The Clock splices more than 10 000 film clips into a 24‑hour loop, synchronised to real time; viewers, trapped between cinema and chronometer, are made acutely aware of passing minutes—“We’re much happier when we don’t have to think about time,” Marclay concedes (Marclay, 2010).

Ryoji Ikeda, test pattern [nº13], audiovisual installation, 2017

Where my painting investigates the tension between human and machine rationality, Ryoji Ikeda’s test pattern pushes machine‑driven data to the limit, compelling the body to endure the sublime. Arbitrary data is instantaneously trans‑coded into black‑and‑white 0/1 bands accompanied by infra‑/ultrasonic pulses; stripes flicker at 60–120 fps, sonic bursts batter the ear—a crystalline precision bordering on violence. Ikeda terms it a “data stress test” (Ikeda, 2013). “Beauty is crystal… the sublime is infinity,” he explains, echoing Lyotard’s and Newman’s discourse on presenting the unpresentable (Lyotard, 1982).

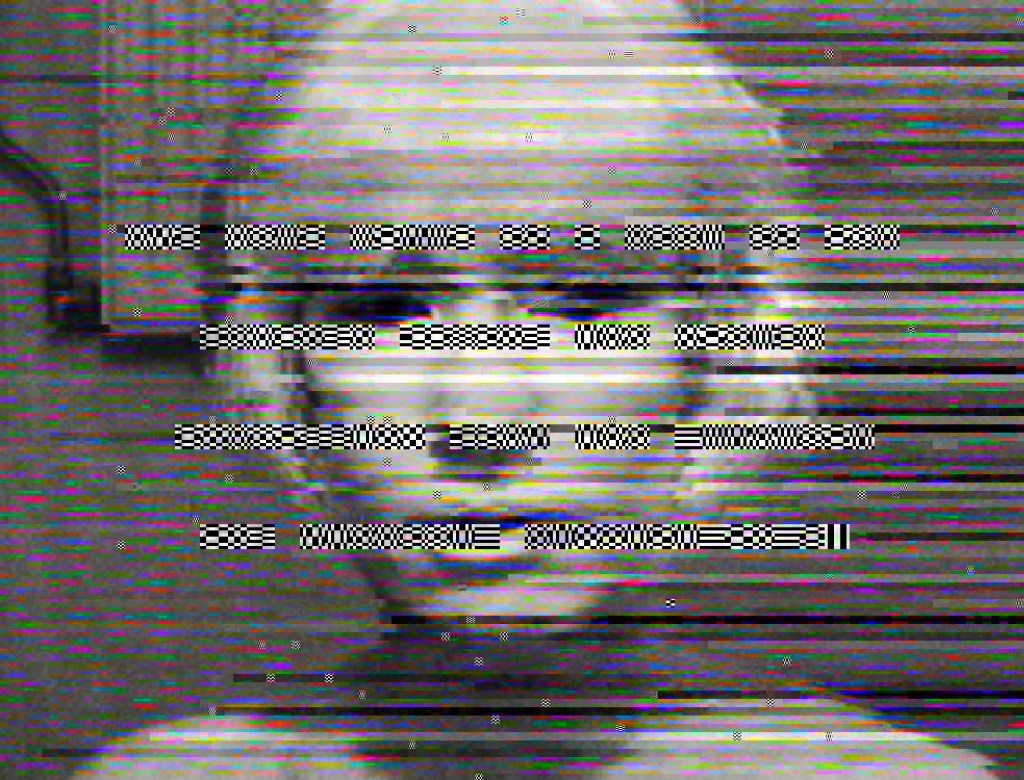

Rosa Menkman, A VERNACULAR OF FILE FORMATS, 2009 – 2010

Contrary to Ikeda’s process of magnification, Rosa Menkman turns her attention to the “accident” itself. In The Glitch Moment(um), she defines a glitch as “any perceptible distortion that breaks a system’s normal state.” These distortions not only correspond to Virilio’s notion of the “inevitable accident,” but also act as wedges that shatter the comfortable UI (User Interface) and expose the black-box code beneath. She terms this approach “Constructive Glitch”: using malfunction to reveal power structures and acceleration logics, thereby forcing audiences to reassess the workings of their media (Menkman, 2011). In doing so, she once again disenchants what has been called “technological re-enchantment.”

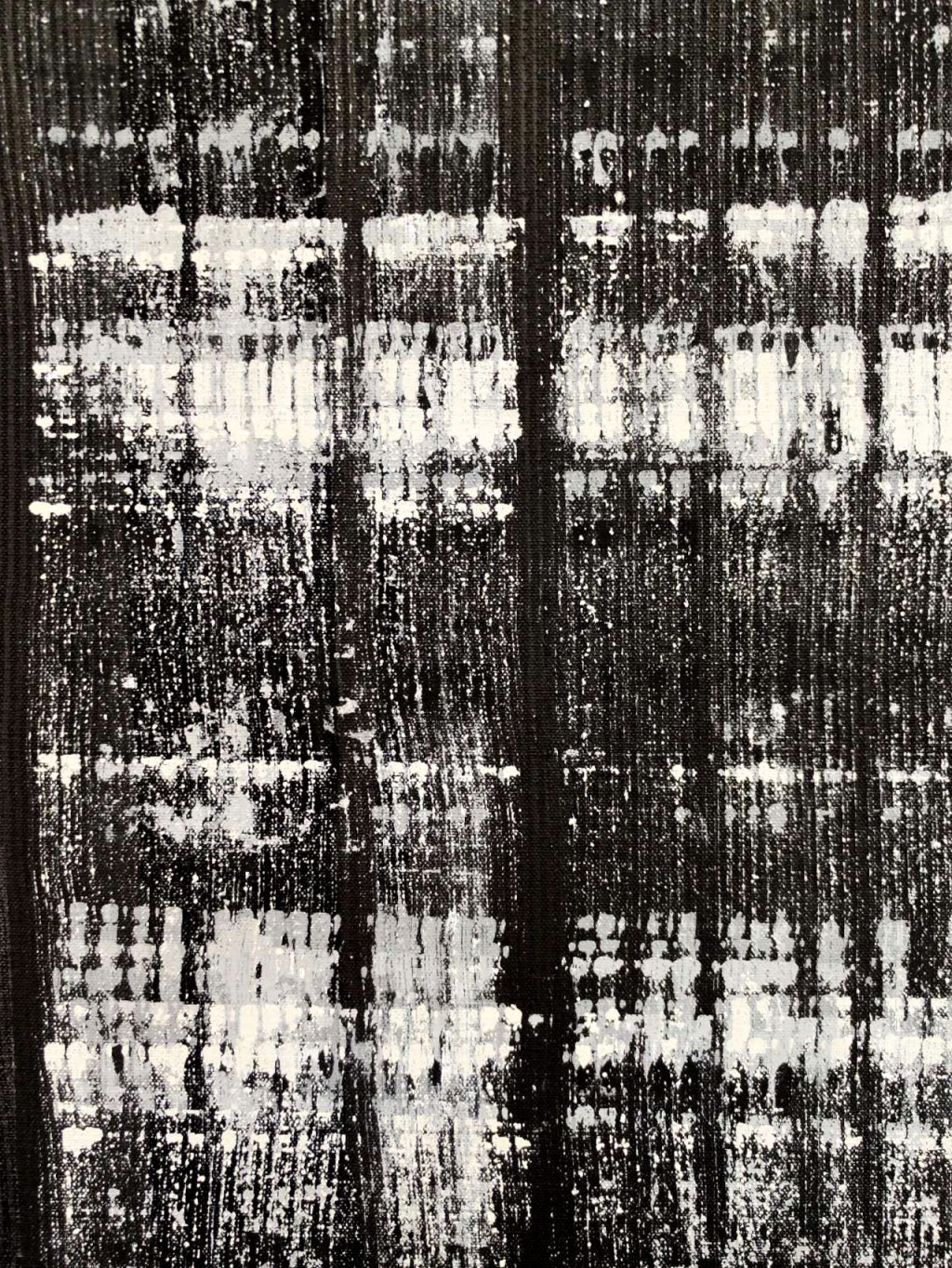

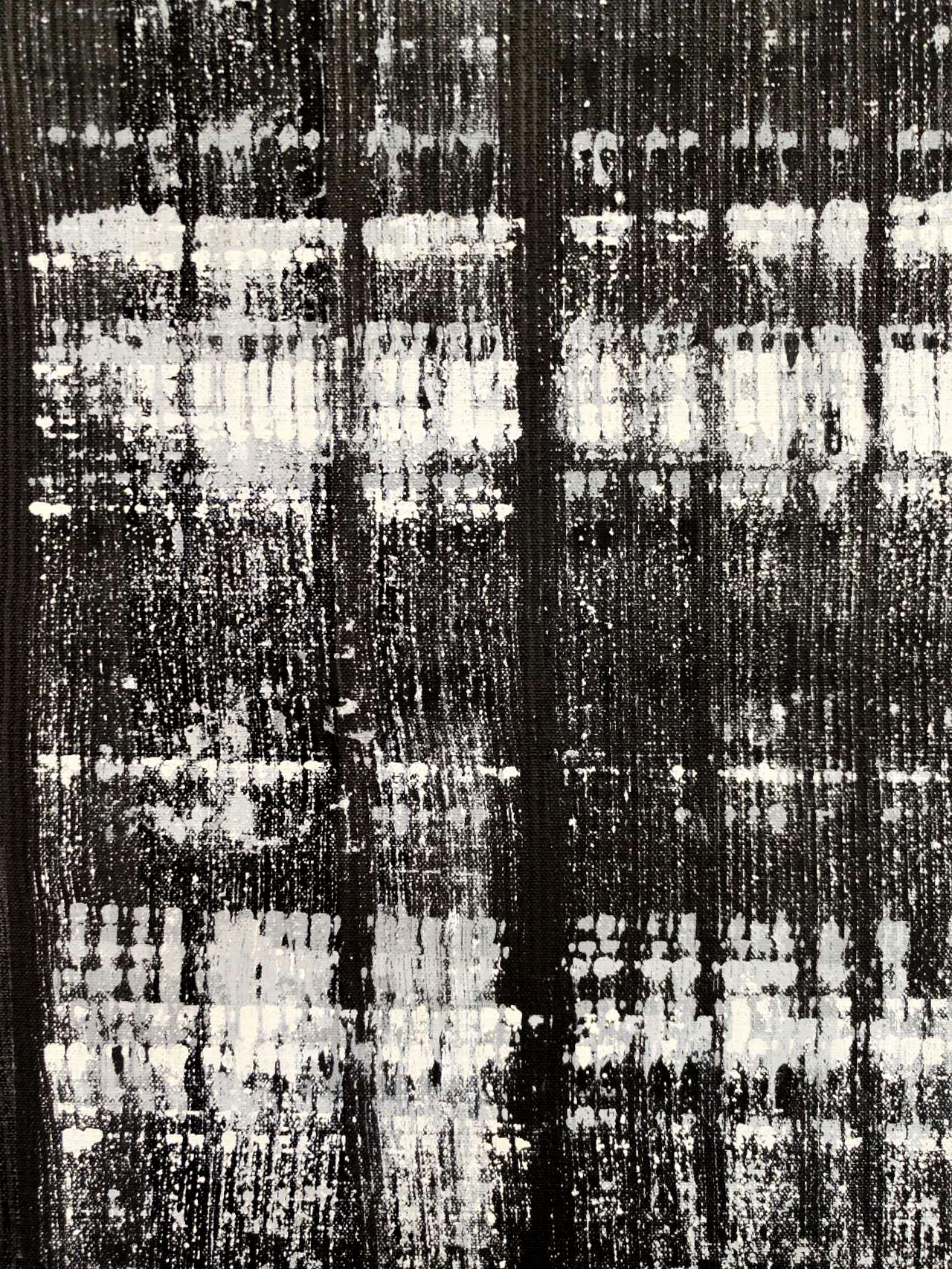

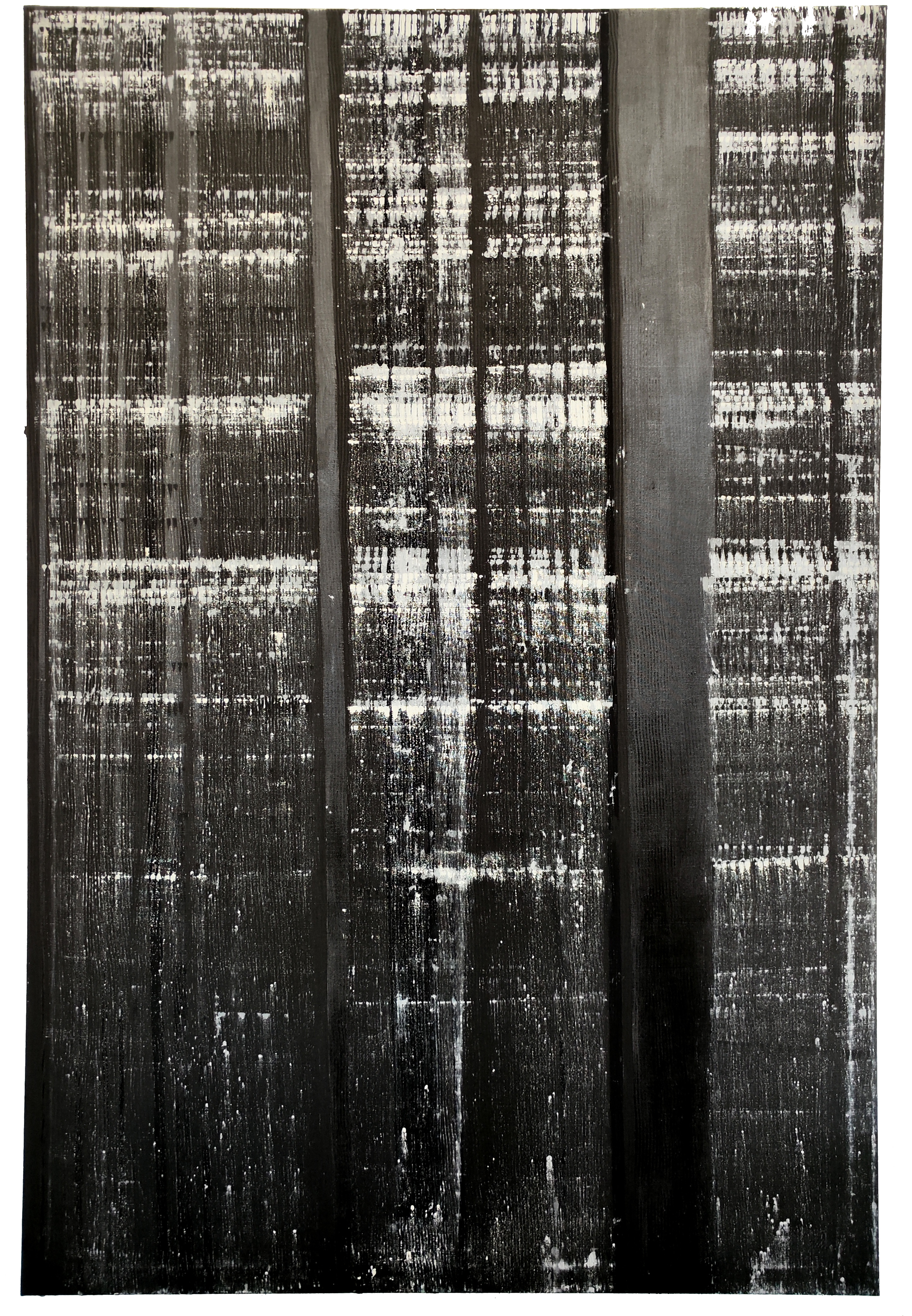

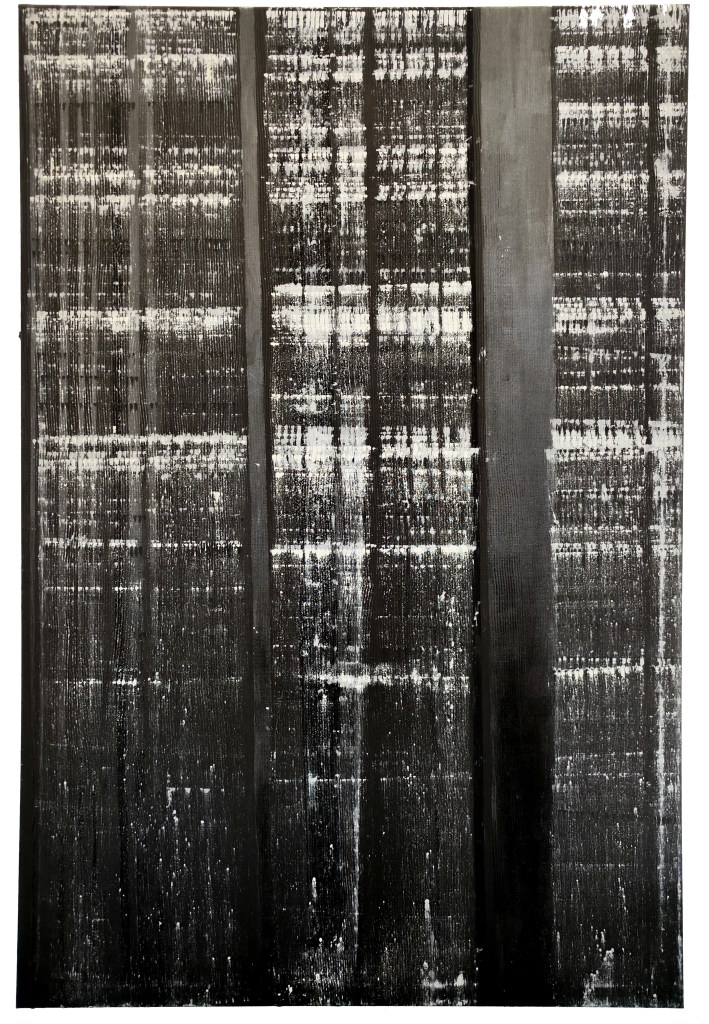

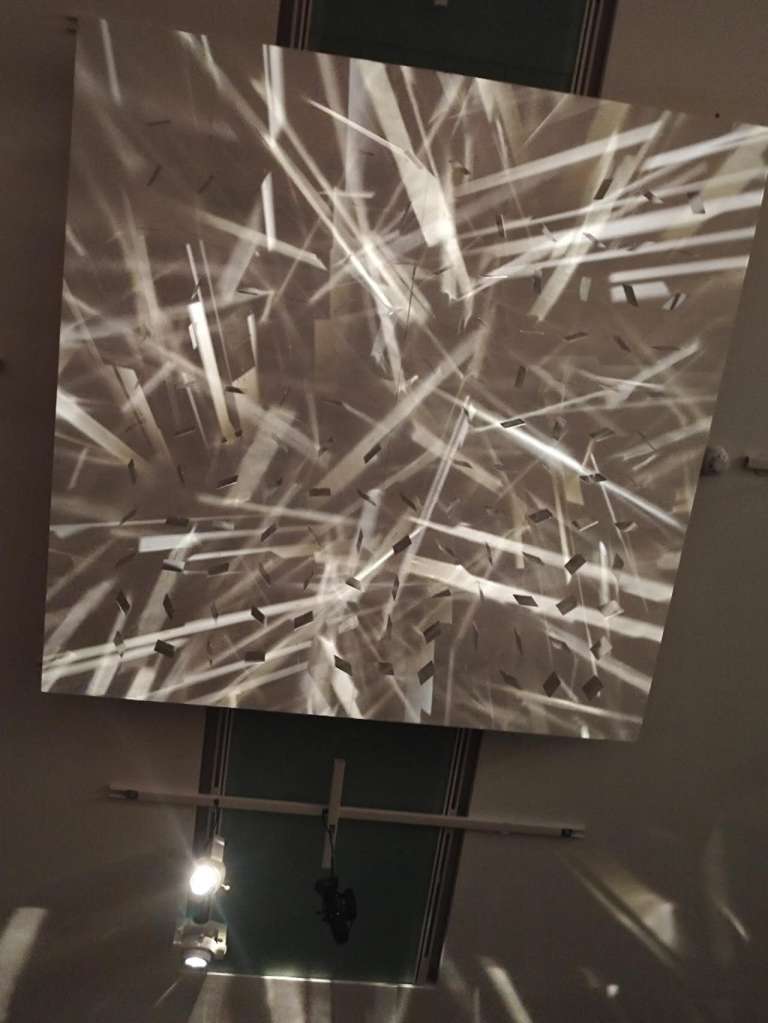

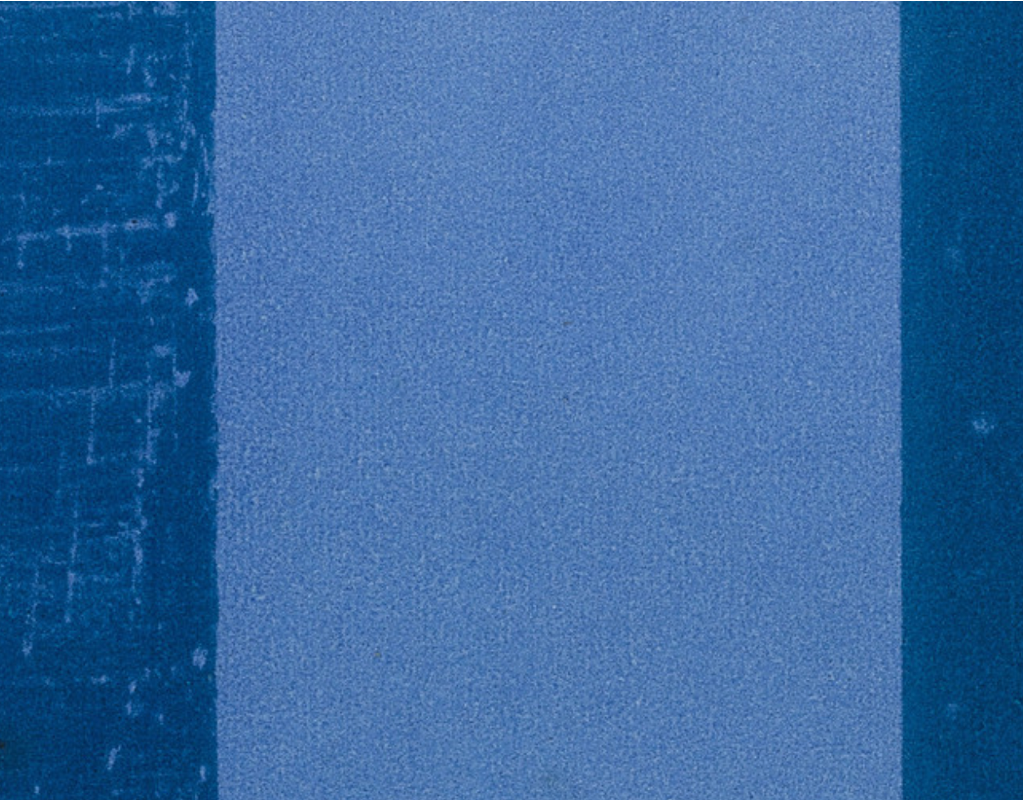

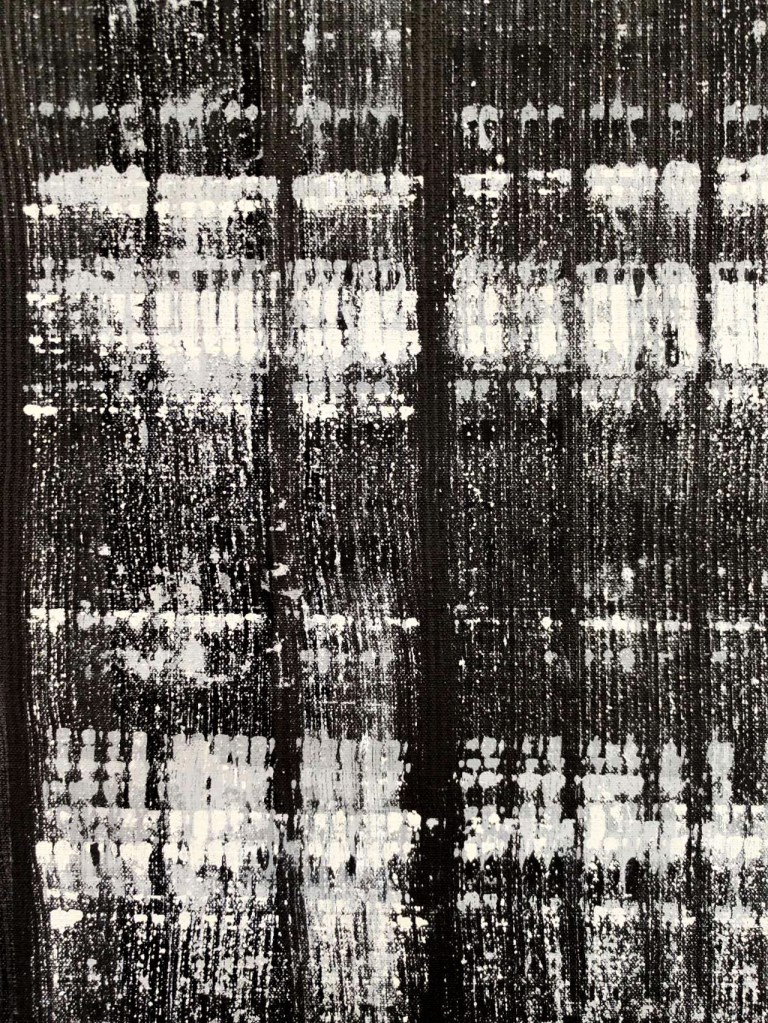

De Tang, 0/1-2, detailed view, Acrylic on Canvas, 2025

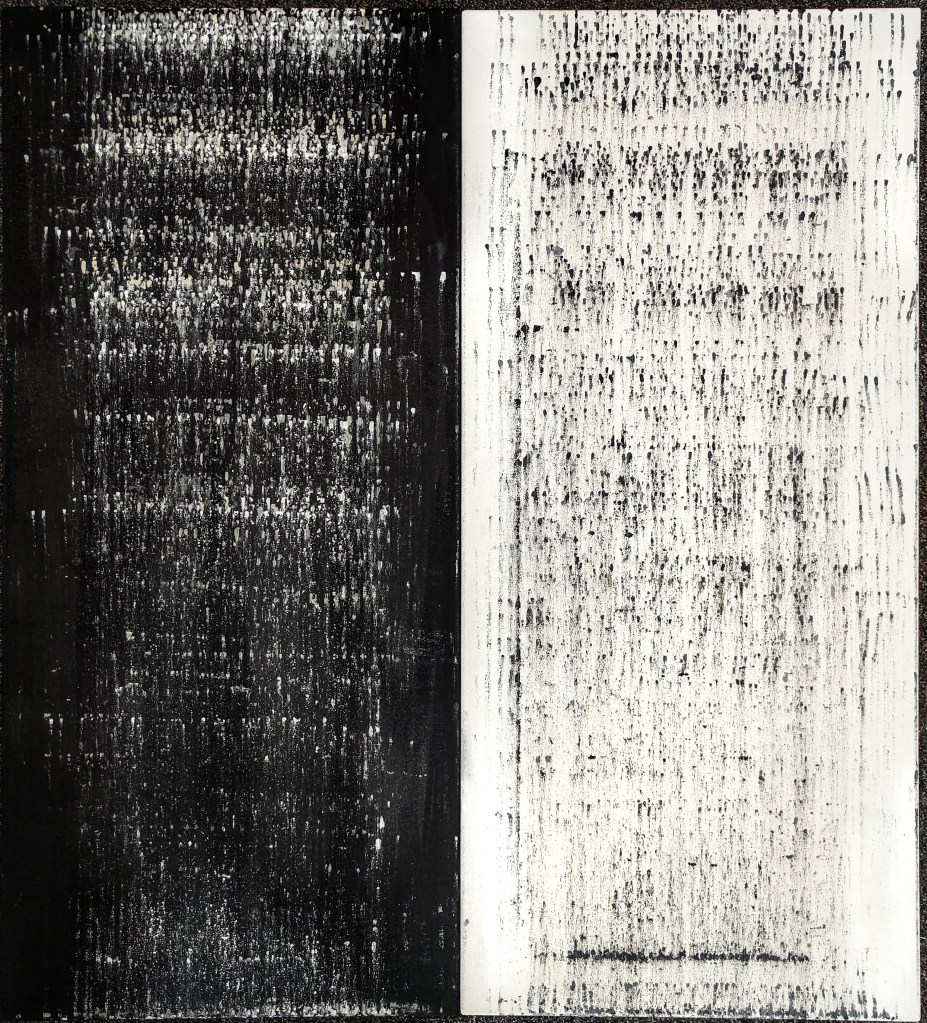

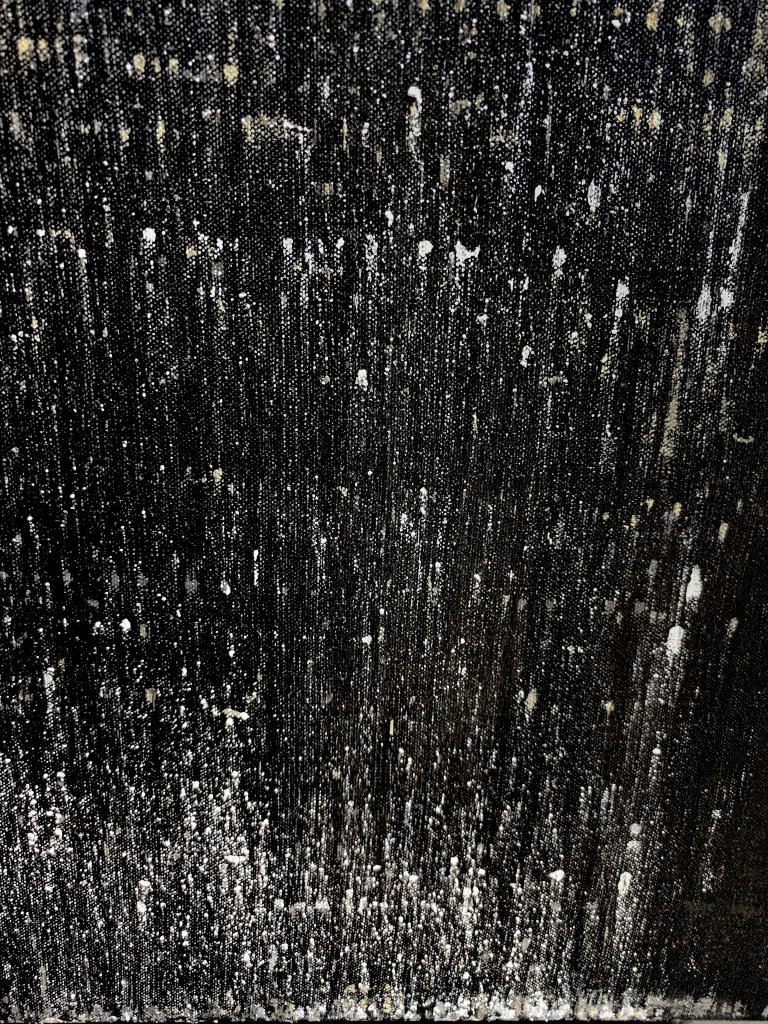

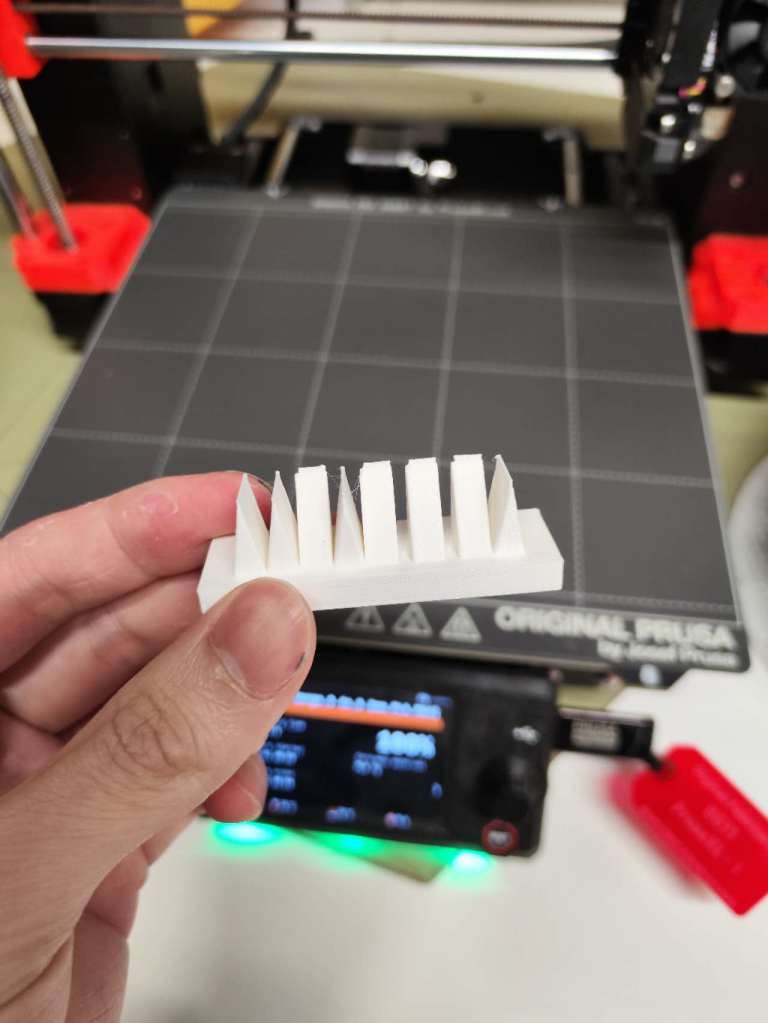

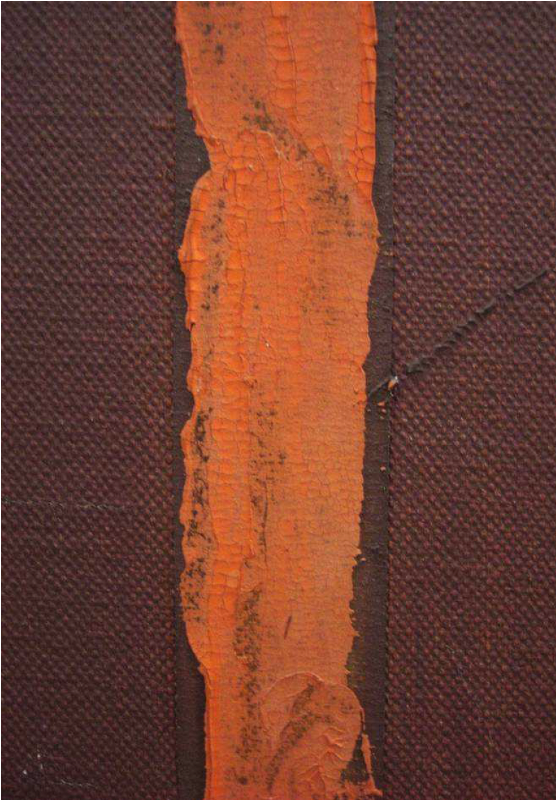

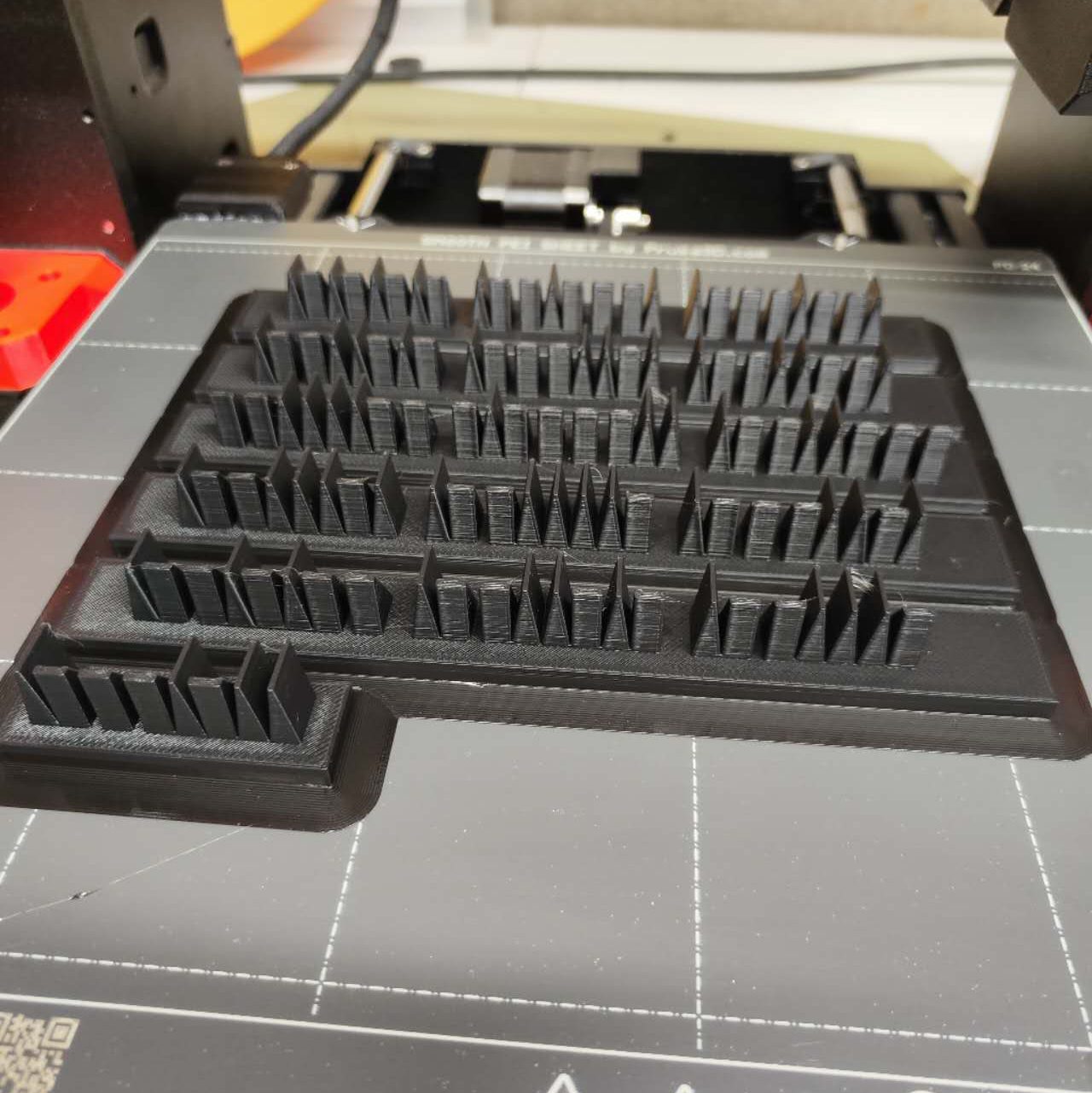

Therefore, , I adopt binary code as medium: it is both the underlying code of new media and the smallest unit of information transmission. I convert words into UTF-8, then into 3D-printed modular brush heads—thick blocks for 1 and thin blocks for 0—materializing a form of “re-encoding.” In the piece 0/1-1, I translate the words “consume” and “produce” into UTF-8 binary. For example, the letter P is 01010000, so my brush head sequence becomes “thin-thick, thin-thick, thin, thin, thin, thin.” I act as a component in a “rational factory,” endlessly stenciling this most authentic language.

In other words, when we post a message via phone or another device, we type our words on a screen and keyboard, while behind the user interface runs code that most people cannot read. If Rosa Menkman exposes hidden structures by creating “glitches,” I mimic the structure itself: my body becomes the printing mechanism, a human printer transferring characters and information. Like a cog in a rational machine, my mechanical labor symbolizes the endless copy-and-paste of its underlying parts. Yet, because my arm cannot reproduce itself perfectly, I inevitably introduce variations in position, angle, and pressure—millions of tiny white points accumulate on the surface, and the viewer faces what looks like a snowy, malfunctioning screen.

Put differently, I am not consciously manufacturing an “accident.” Rather, I bring the medium itself to the forefront: from encoding and presetting to operation, I emulate the accelerating rational machinery of society, but the true activating variable is “me”—the one who continually generates deviation.

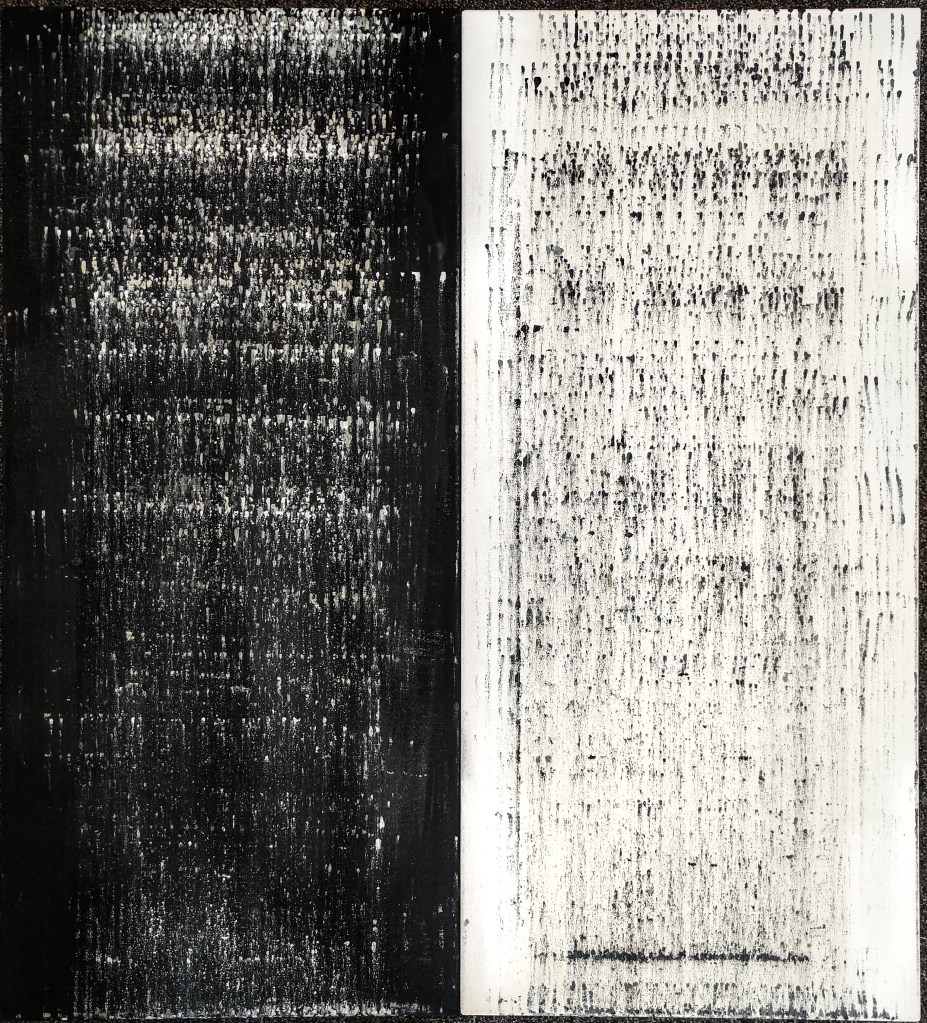

De Tang, 0/1-1, Acrylic on Canvas, 2025

Chromatically I strip decoration, retaining only black and white—barcode starkness, the binary absolutism of 0/1—yet greys and noise inevitably seep through, challenging quantification’s dominion.

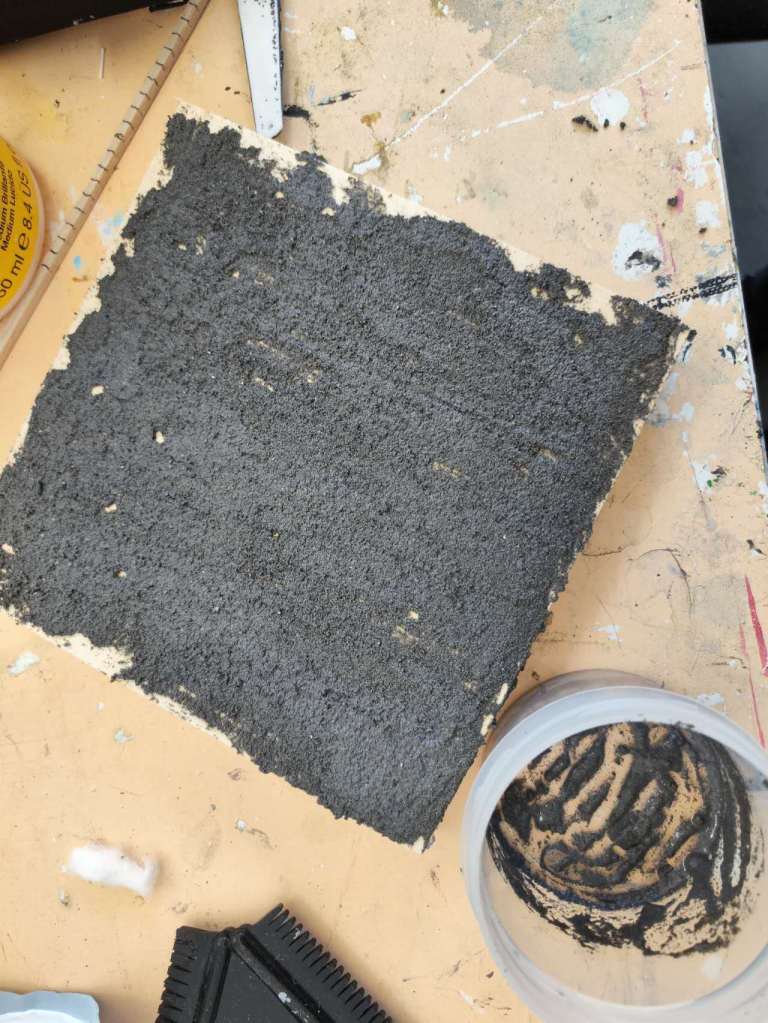

In terms of material selection, I experimented with various pigments and media to reveal the temporal traces left by the materialization of information. Following Richard Wollheim’s theory of “Configurational/Recognitional” seeing—where a painting functions both as an image and as a material object—I repeatedly adjusted the ratios of pigment, thickener, and thinner in my acrylic mixtures. My aim was for the paint, under the friction of my brush, to record marks of force and mechanical abrasion, avoiding gravity-driven drips like those in drip paintings, while also preventing paint so thick that it wouldn’t spread.

The first-generation brush head—hand-carved wood strips bound with hot glue—was discarded due to its excessive randomness. The second-generation 3D-printed head, though precise, ignored the drawing angle and failed to hold paint reliably. Only with the third-generation, which incorporated an angle correction mechanism, did the “printing” of information run smoothly.

Every technical adjustment forms a chain of deceleration that drags abstract code into substance, loading each stroke with temporal resistance and allowing viewers, while deciphering that broken field, to feel the irrevocable gap between media machinery and organic agency.

Gallery

De Tang, 0/1-1, Acrylic on Canvas, 45cm x 100cm, 2025

De Tang, 0/1-2, Acrylic on Canvas, 100cm x 160cm, 2025

Process Photograph

Contexts

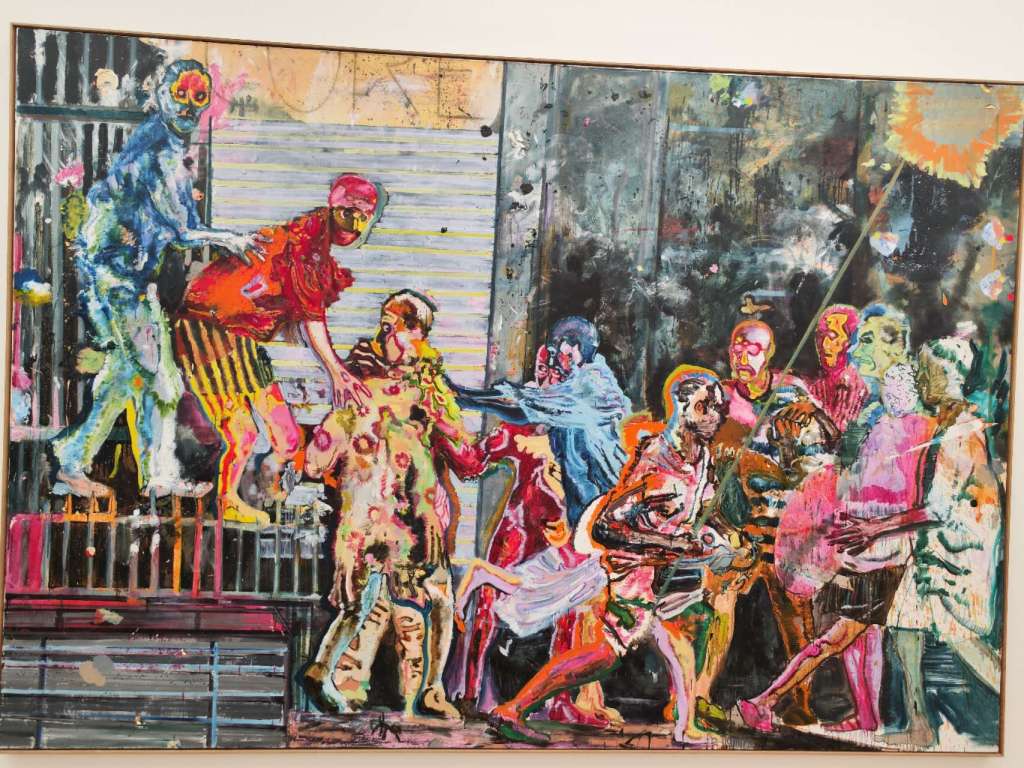

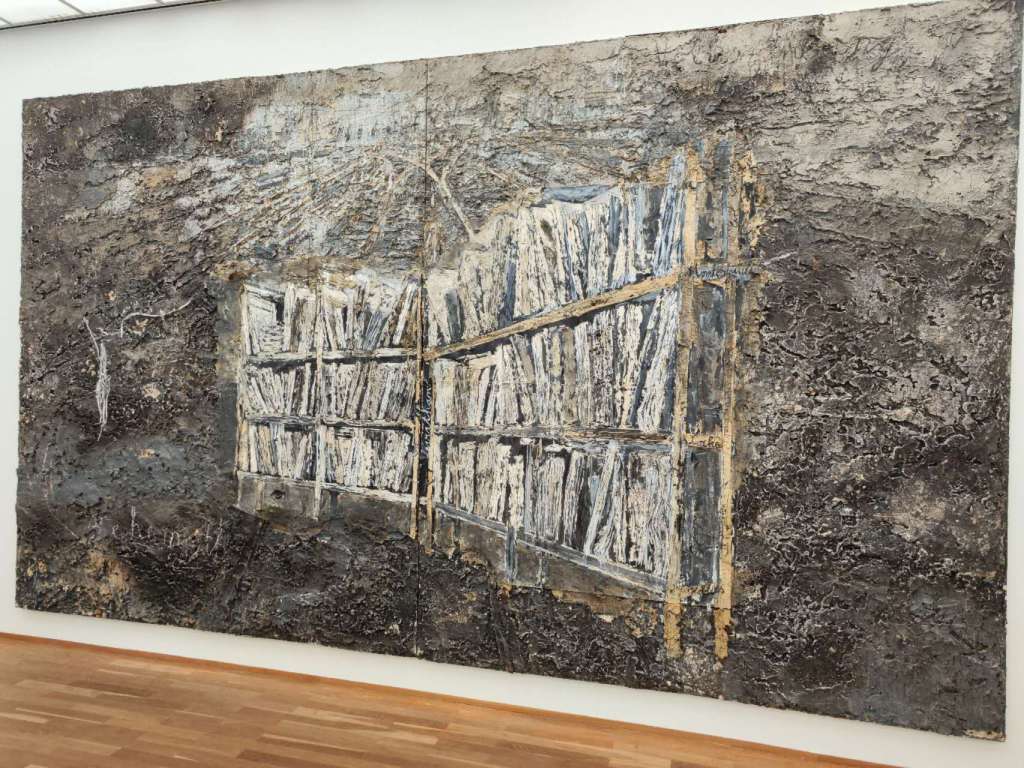

Hamburger Bahnhof Gallery

In mid-May, I visited the Hamburger Bahnhof gallery in Berlin, Germany. The many artworks and their creators sparked my reflection, and I viewed these paintings through the perspective of “efficiency–materiality–digital media.” What impressed me most was Anslem Kiefer’s colossal mural: by deploying materials such as cement, earth, steel, wood, and fabric, it powerfully asserts its own presence. Rather than merely looking at a painting, you step into a material world. Standing before it is not just a visual experience but a bodily one—an encounter with space and delayed perception that the “virtual image” on a smartphone screen can hardly replicate.

Another highlight was Daniel Richter. His work begins with photographic images, which he then transforms into semi-abstract paintings. In Slow Painting: Contemplation and Critique in the Digital Age, the author draws on Richter’s example to describe the method and necessity of “slow imagery.” He contrasts the “speed” of news media with Richter’s slower approach, invoking Dovey’s concept of simultaneous adaptation—juxtaposing two or more radically different source materials within a single work to de-narrativize it and invite the viewer into active association and analysis.

The curatorial space at Hamburger Bahnhof is fascinatingly laid out like a series of train carriages. Each “carriage” opens onto a long corridor in which no trace of the exhibition is visible; only after passing by each compartment and then turning into it can you finally see the works on display. This immediately brought to mind the information barriers of the internet: browsing in a media site or search engine feels like standing in that corridor—you know there’s content beyond, but have no idea what it is until you “turn the corner” and enter that closed-off little world to discover its specifics.

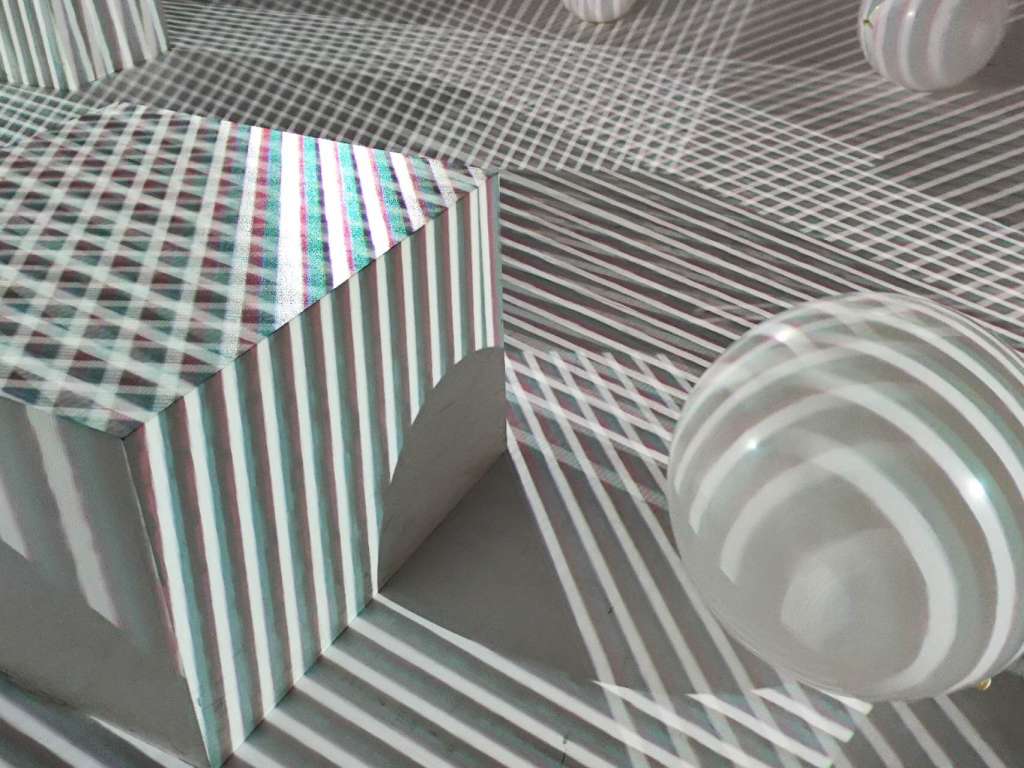

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet

In April, I visited Tate Modern’s major exhibition Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet. Rather than relying on today’s high-tech gadgets, the featured artists worked with vintage appliances and early home computing systems from the 1970s through the 1990s. Tracing a lineage “from the birth of op art to the dawn of the internet age,” the show celebrated pioneers of optical, kinetic, programmed, and digital art—those who first explored immersive sensory environments through mathematical principles, motorised components, and new industrial processes.

Throughout the galleries, I encountered psychedelic installations built from buzzing electric motors, flickering CRT screens, and custom-built circuitry. Many artists deliberately subverted their own machines—intentionally generating visual glitches, endlessly oscillating images, and blinding flares of light—to challenge our expectations of “perfect” technology. A highlight was a series of early computer-generated graphics: unlike today’s AI-driven imagery, these were the product of direct machine calculation, with every pixel plotted by algorithms running on home computers.

By juxtaposing these works with the surrounding gallery architecture, the exhibition powerfully evoked our current condition of information overload. Just as Electric Dreams invited viewers to step inside the imagined “visual language of the future,” these artists anticipated how technology could both extend and disrupt human perception. Supported by partners including Gucci, Anthropic, and the Hyundai Tate Research Centre, this ambitious retrospective reminded me how those early innovators laid the groundwork for today’s digital and interactive art.

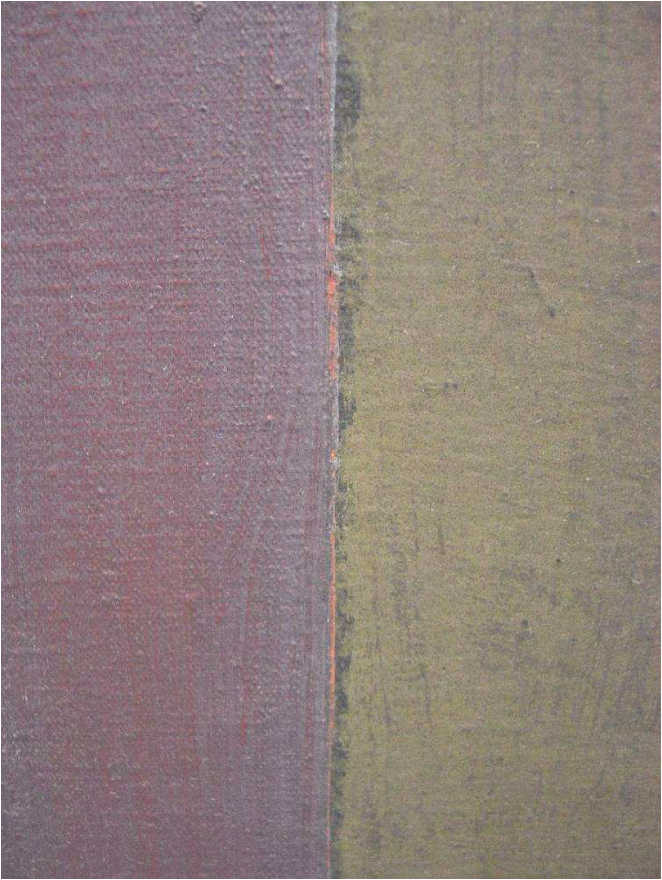

From Ruler to Tape: Stops and Starts in the History of Painted Abstraction – Pia Gottschaller

I drew on Gottschaller’s “From Ruler to Tape” article when preparing my talk on Process–Technology because it crystallized for me how the choice of tool encodes an artist’s stance toward precision and spontaneity.

Building on Gottschaller’s survey of twentieth-century abstraction, it talks that the debate over rulers and tape was more than a mere technical squabble—it signaled a ideological divide. From Kandinsky’s “inner essence” approach to Rodchenko’s “spatial sharpness,” abstractionists split into those who prized the expressive spontaneity of the handmade and those who championed the rigor of industrial precision . This split persisted even as innovations like pressure-sensitive tape emerged in the 1930s, offering unprecedented edge-making efficiency. Yet tape’s mechanical perfection was embraced or resisted according to where an artist stood on the romantic-metaphysical versus rational-mathematical spectrum .

Several case studies illustrate how tool choice encoded aesthetic stance. Mondrian, for example, despite experimenting with straightedges and templates, never actually painted with tape, preferring to regain control through painstaking hand-adjustment and reworking of his renowned grids . By contrast, Barnett Newman not only used tape on paper as early as 1946 but incorporated actual strips into seminal works like Onement I (1948), letting the bleed of cadmium paint around masking-tape edges both assert and soften the band’s presence—an embodiment of his belief in line as a “pure means of conveying emotion” .

Gottschaller’s article also discusses how later figures such as Rothko, Riley, and Martin navigated the same tools differently: Rothko adopted tape for defining outer perimeters of his Houston Chapel canvases yet continued to modulate and purge seepage to maintain his signature gradients ; Riley, wary of tape’s ridges, worked with ruling pens to ensure a humanized line ; and Martin moved between pencil-guided freehand strokes and taped edges according to the painting’s evolving needs .

These insights directly shaped my own workflow: rather than lean wholly on mechanical brushes for dead-on straight lines, I allow subtle, variable imperfections to slip in—breathing a bit of living warmth into otherwise rigid forms.

Glossary of Key Concepts & Terms

Click to un/fold

| Term / Phrase | Concise explanation | Principal source |

|---|---|---|

| Dromology | Dromology—from the Greek dromos, “racecourse”—is the study of speed and its effects on society. Virilio insisted that speed is never just a neutral ratio of distance to time; it is a form of power that reorganises perception, authority and even identity. | Virilio 1977 |

| Technological re-enchantment | The reversal of Enlightenment dis-enchantment whereby digital technology becomes a new generator of wonder. It operates on two intertwined planes: (1) Everyday UX–platform magic — friction-free interfaces, push-notification affect and algorithmic efficiency cocoon the user in a seamless, seemingly benevolent world, masking the disciplining power of the apparatus (Virilio 1995; Manovich 2001). (2) Techno-theological imagination — transhumanist discourses, mind-upload promises and AI “singularity” narratives recast data and code as salvific forces, supplying fresh metaphysics after the collapse of older faiths (Antosca 2022). In both registers, speed itself becomes the new aura: screens turn into altars, users into believers. | Derived from Virilio 1995; Manovich 2001; Antosca 2022 |

| Apparatus(Foucault) | A network of discourses, institutions and technologies that disciplines bodies and perceptions beneath a human-centred façade. | Foucault 1977 mention |

| Medium as Cognition | The idea that media are not neutral conduits but environments that co-produce subjectivity and meaning. | Author’s framing (Medium as Cognition) |

| Digitization | Converting continuous, uncertain reality into discrete, measurable data. | Manovich 2001, p. 52 |

| Algorithmic manipulation | Infinite copying, editing and recombination of digital data via software procedures. | Manovich 2001 |

| Algorithmic / Rational factory | Metaphor for a socio-technical system where algorithm = reason and efficiency = ultimate telos. | Author’s synthesis (Medium as Cognition) |

| Social Acceleration | Rosa’s three-fold speed-up of technology, social change and life-pace underpinning modernity. | Rosa 2013 |

| Chronometric / Abstract time | Time fragmented into quantifiable units that can be priced and traded like battery charge. | Rosa 2013; Virilio 1986 |

| Temporal Sovereignty | Rosa’s call for individuals & institutions to reclaim control over their own rhythms. | Rosa 2013 |

| Resonance | A relational mode—touchable, answerable, transformable—countering the drive for total control. | Rosa 2020 |

| Integral Accident | Virilio’s thesis that each technological leap creates a new, systemic form of catastrophe. | Virilio 1995 |

| Grey Ecology / Speed-pollution | Treating velocity itself as an environmental contaminant that degrades perception and social fabric. | Virilio 2009 |

| Constructive Glitch | Menkman’s notion of purposeful malfunction that exposes hidden power and code, provoking critical awareness. | Menkman 2011 |

| Data stress test | Ikeda’s term for bombarding the senses with maximised binary patterns and sound to reveal human–machine thresholds. | Ikeda 2013 |

| Presenting the Unpresentable | Lyotard’s postmodern sublime: evoking the infinite through forms that signal their own limits. | Lyotard 1991 |

| Configurational / Recognitional seeing | Wollheim’s dual account: a painting is apprehended both as material surface and representational image. | Wollheim 1987 |

| Binary re-encoding | Converting words into UTF-8 0/1 sequences and materialising them via 3-D-printed brushes. | Artist’s method (Medium as Matter) |

| Chain of deceleration | The series of material frictions that slows digital code into tactile time traces. | Author’s conclusion (Medium as Matter) |

| Dynamic stabilisation (modern society) | Hartmut Rosa’s definition of modernity: “A modern society … can stabilise itself only dynamically; it requires constant economic growth, technological acceleration and cultural innovation in order to maintain its institutional status quo.”The system must keep moving faster just to stay structurally unchanged. | Rosa 2020 |

| Experience machine | Robert Nozick’s thought-experiment: a perfect simulator offering limitless pleasure. Most people, he argues, would refuse to plug in—showing we value authenticity, agency and connection over manufactured happiness. Frequently invoked in media theory to critique friction-free UX and “happiness-machine” culture. | Nozick 1974 |

| Glitch | A perceptible malfunction—data drop-outs, pixel bleed, audio stutter—that momentarily exposes the material substrate of a digital system. It interrupts the “seamless” user flow and opens a window onto hidden code, protocols and power relations. | Menkam 2011 |

Reference

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

Hsieh, T. (1981) One Year Performance 1980–1981 (Time Clock Piece) [artwork]. New York: Artist’s archive.

Ikeda, R. (2013) test pattern [installation]. Tokyo: Studio Ryoji Ikeda.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1982). PRESENTING THE UNPRESENTABLE: THE SUBLIME. [online] Artforum. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/features/presenting-the-unpresentable-the-sublime-208373/.

Manovich, L. (2001) The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marclay, C. (2010) The Clock . London: White Cube.

Menkman, R. (2011) The Glitch Moment(um). Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

Nozick, R. (1974) Anarchy, State and Utopia. Basic Books, pp. 42-45.

Rosa, H. (2013) Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rosa, H. (2020) The Uncontrollability of the World. Cambridge: Polity.

Virilio, P. (1997) Open Sky. London: Verso.

Virilio, P. (2009) Grey Ecology. New York: Atropos.

Virilio, P. (1986) ‘The Overexposed City’, in Solomon, D. (ed.) Zone 1/2: The Contemporary City. New York: Urzone, pp. 14‑31.

Wollheim, R. (1987) Painting as an Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Renwu Magazine (2020) ‘Delivery Riders, Trapped in the System’, People, 8 September.

Antosca, A. R. (2019) ‘Technological Re-Enchantment: Transhumanism, Techno-Religion, and Post‑Secular Transcendence’, Humanities and Technology Review, 38(2), pp. 1–28.