This is a progress report article that primarily discusses recent reflections, research, and artistic practices. Given the title "An Inquiry," it serves more as a theoretical exploration. The specific practical aspects will be detailed in subsequent records of artistic practice.

Artist Statement

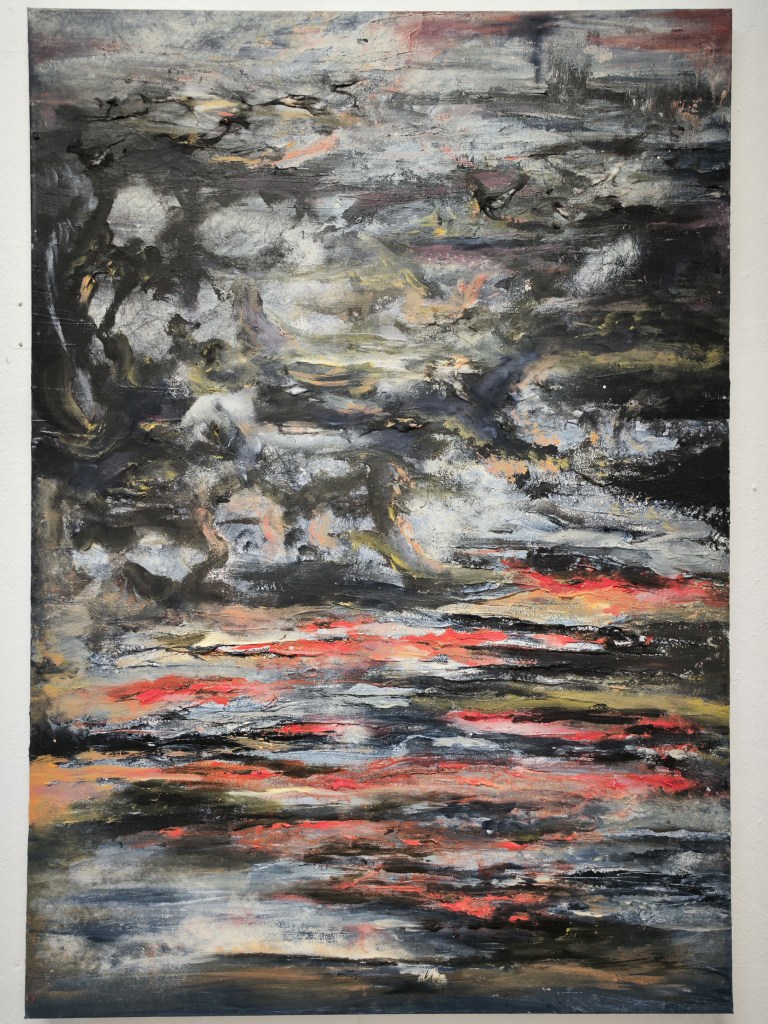

My artistic practice stems from an existential inquiry, declared simply yet profoundly as “I Exist.” Through acrylic painting and mixed media, I create abstract landscapes that engage with the absurd and the sublime—not as external spectacles but as deeply personal and internal experiences.

Unlike the traditional sublime, which relies on overwhelming natural grandeur, my work explores a postmodern sublime—one that emerges from the contradictions of contemporary life: the longing for meaning amid an accelerating world that continuously erases uncertainty. As Paul Virilio states, “You don’t have speed, you are speed”—in a world consumed by rapid updates and ephemeral identities, I attempt to slow down. My paintings become spaces for contemplation, resisting easy interpretation and instant consumption.

I construct immersive visual environments where layered paint, ambiguous forms, and unconventional materials evoke the instability of perception and thought. Inspired by artists like Fabian Marcaccio, who transforms painting into sculptural, almost architectural forms, I experiment with textured surfaces—sometimes incorporating fabrics, foam, or sculptural elements—to push painting beyond its traditional confines. Light, too, plays a crucial role in my work: I explore its presence and absence, investigating how it shapes space and perception.

Rather than presenting a fixed narrative, my paintings suggest a constant state of flux—a confrontation with uncertainty. As Barnett Newman famously declared, “The sublime is now.” It is found in the present moment, in the tension between knowing and unknowing, in the struggle to make sense of an elusive reality. In my work, the sublime is not about achieving transcendence but about remaining in the question and engaging with the unresolved.

Gallery

A Documentation of current art practice

My Artistic Practice, Methods, and Reflections

One of the core goals of my artistic practice is to create new visual experiences and multi-sensory engagement through the fusion of various media and pigments. In earlier projects, I experimented with the oppressive scale of large paintings, integrating spray foam to produce a sculptural painting effect. The foam extended beyond the boundaries of the canvas, bursting forth with a sense of vitality, accentuated by red paint.

Untitled, 2024, mixed media, 100cm x 70 cm

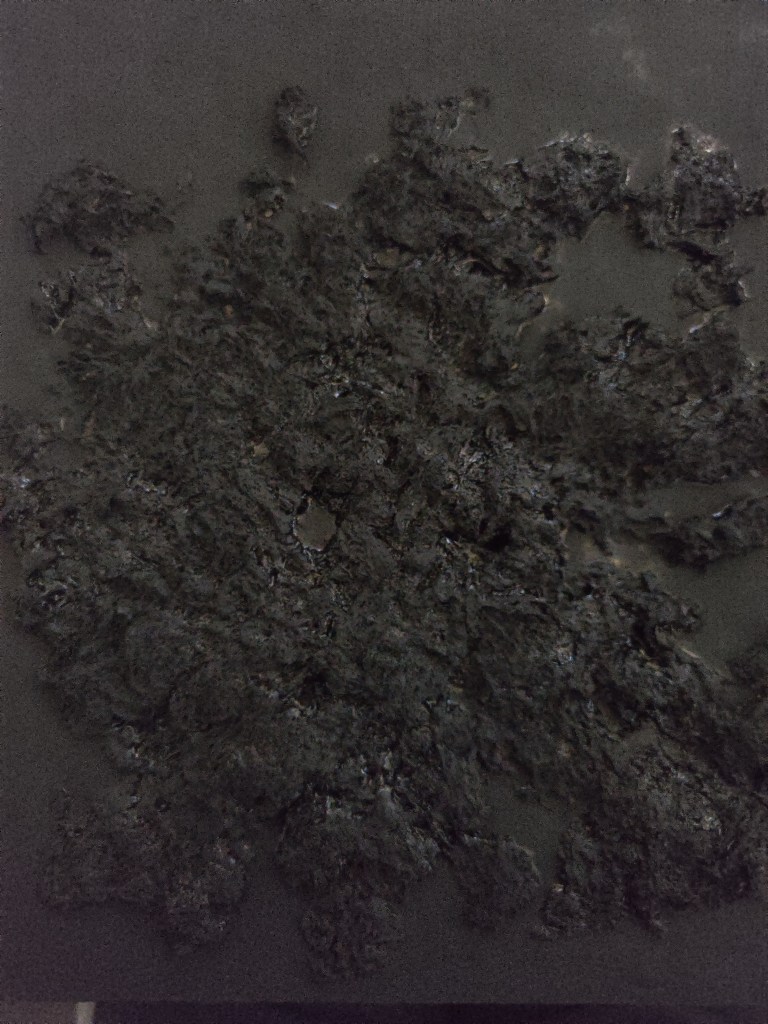

Following this, I experimented with materials such as wool and velvet, blending them with acrylic paints and mediums to create a texture that resembled moss clinging to the canvas. During this process, I came to realize that as I intentionally incorporated different materials onto the canvas, these materials began to assert their own presence. For instance, when wool was combined with the canvas, my initial intention of evoking a sense of life transformed into a portrayal of the material’s inherent physicality.

Discovering this materiality required unconventional viewing methods—such as observing from a close, angled perspective, or even touching the surface. To highlight this physicality, I outlined the intentionally uneven textures I had created. This act of “re-presentation” often led to a painting that diverged completely from my original intent, resulting in a wholly new artistic expression.

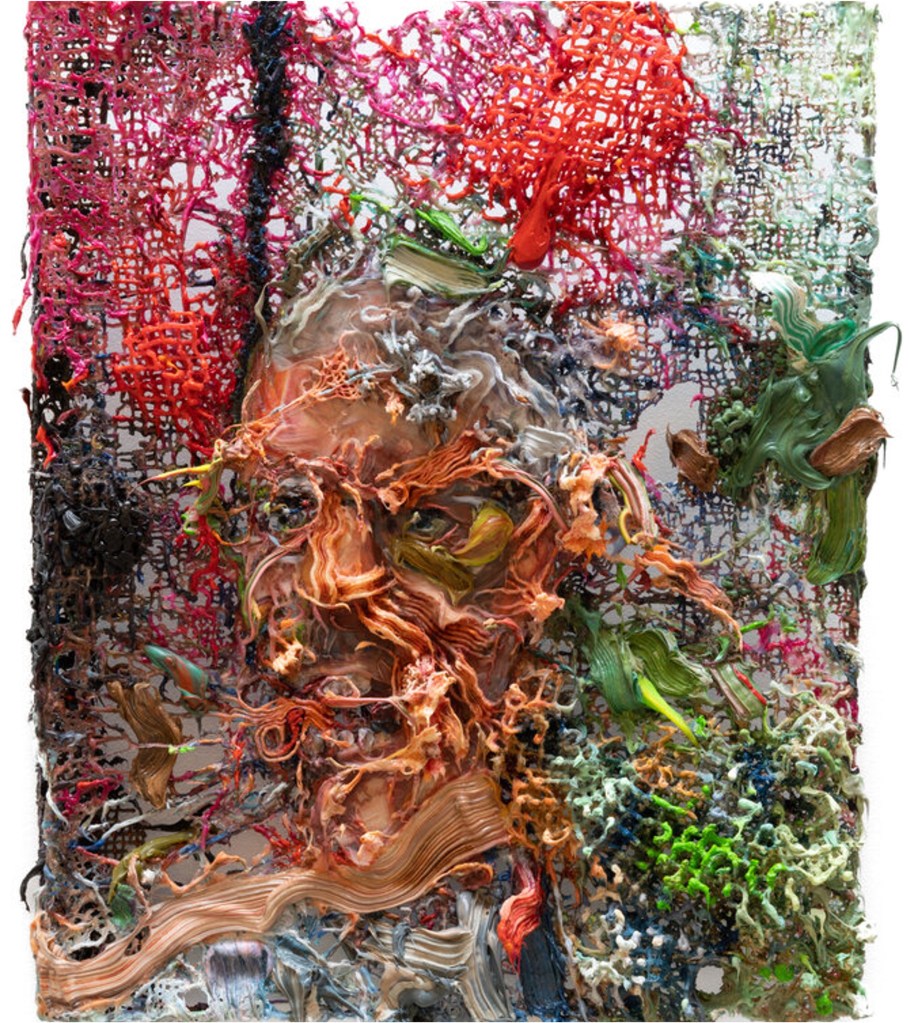

Fabian Marcaccio, Technobrutalist Portrait, 2020–2022

This exploration was partly inspired by Fabian Marcaccio’s Technobrutalist Portrait (2020–2022), a work without traditional framing or canvas. Marcaccio employed silicone, oil paint, and 3D-printed polyurethane to construct a painting where the medium itself became independent (though some steel wires were used for structural support). Additionally, Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe’s essay Technology Sublime further refined my understanding of the material’s autonomy and its role in artistic creation. These influences prompted me to rethink my approach to art-making.

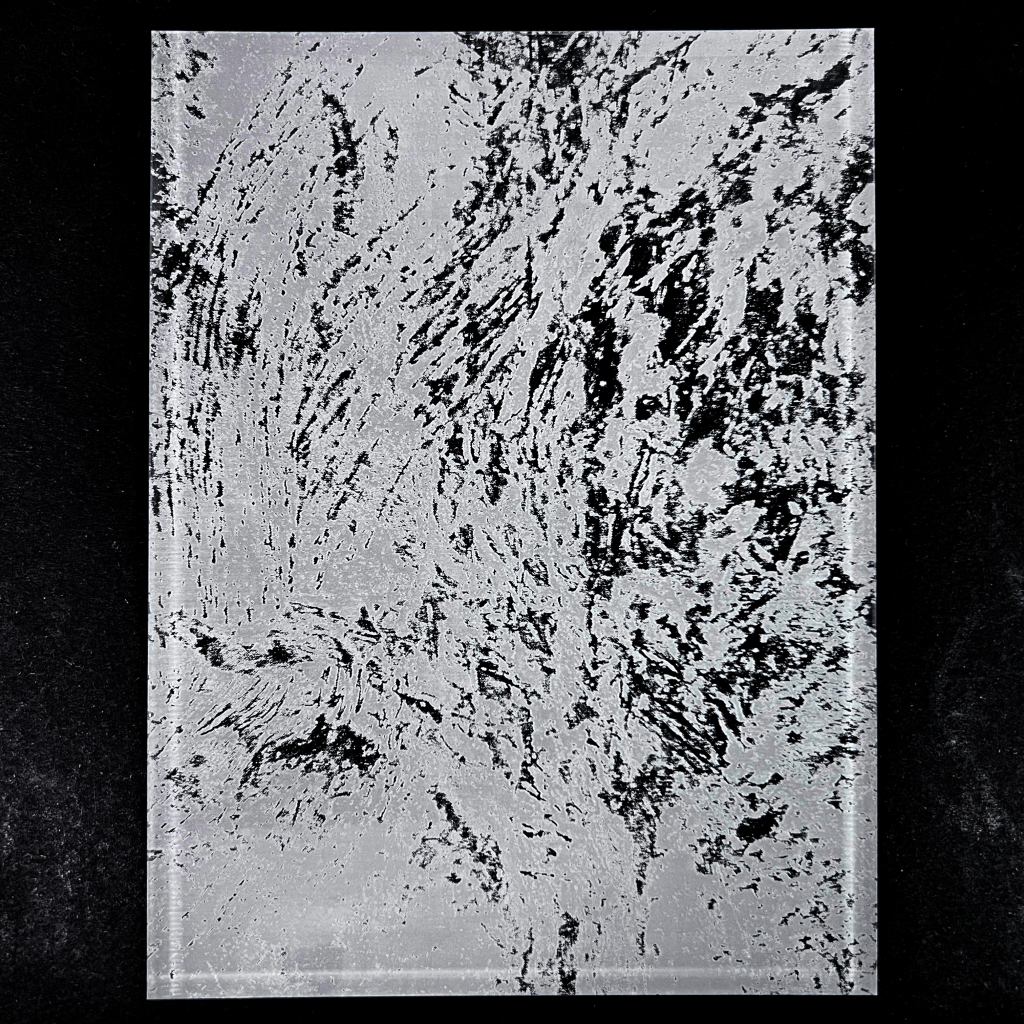

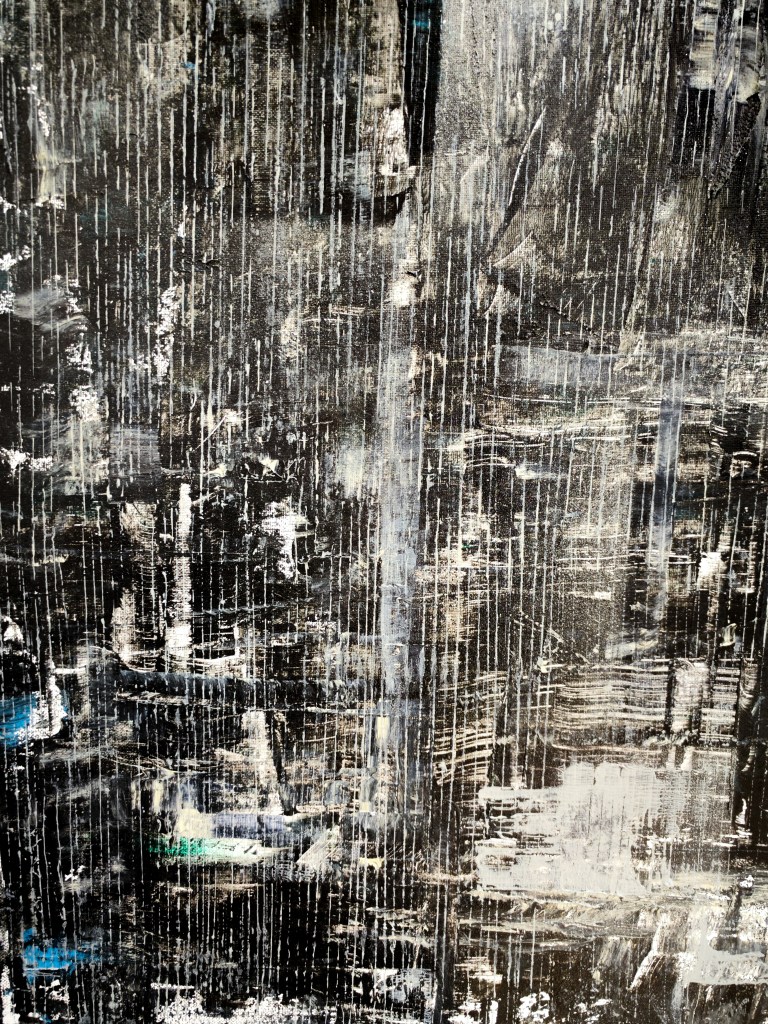

In subsequent experiments, I explored laser etching as a method to reproduce textures. This approach sought to employ a mechanical, non-subjective process to emphasize the materiality of the medium. It also resonated with Gilbert-Rolfe’s notion that technology, as an artistic product, gradually escapes the creator’s control and becomes an independent, uncontrolled “other.”

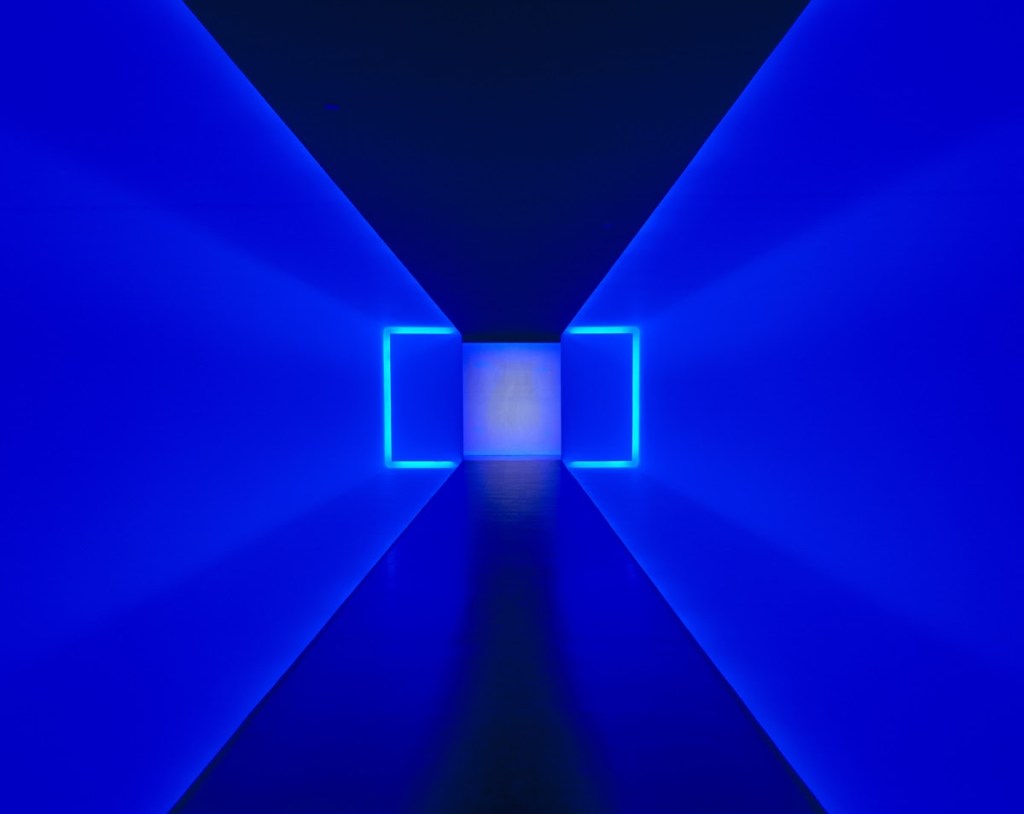

My next shift in experimentation focused on shaping spatial experiences and immersive scenarios. James Turrell’s series on light and space deeply inspired me, revealing how light, as a medium, fills a space much like acrylic paint covers a canvas. In this context, there is no such thing as “natural light”; even the so-called natural has its own color, tinting the entire space like paint. Inspired by this, I attempted to integrate fiber optics into my paintings, embedding light sources within the fibers to make them emit visible colors. However, due to technical limitations, this concept has yet to be fully realized.

James Turrell1999

Pushing the boundaries of light experimentation, I explored its opposite: the absence of light. I sought a pigment capable of absorbing almost all light, such as Anish Kapoor’s Vantablack. Ultimately, I chose CULTUREHUSTLE’s Black 4.0 Paint, which claims to absorb 99.9% of visible light. In my experiments, this paint created a sense of void and emptiness, especially in low-light environments. This discovery opens new possibilities for mediums and experiential effects in my future works.

Critical reflection

Foreword

As mentioned in my previous summary statement, my artistic practice stems from a philosophical inquiry into the self. This section aims to explain why I chose this theme and how my journey from confronting the absurd to embracing the sublime ultimately led to artistic creation. It is worth noting that my art is neither a conclusion of my philosophical inquiry nor an illustration of philosophical ideas. Rather, it unfolds my own existence following this inquiry. Hence, the title of my project: I Exist.

Thomas Pynchon’s novel contains a thought-provoking statement:

“The width of your present, your now … The more you dwell in the past and future, the thicker your bandwidth, the more solid your persona. But the narrower your sense of Now, the more tenuous you are.” (Gravity’s Rainbow, p. 509).

This concept of “temporal bandwidth” inspired me to reflect on the relationship between life, thought, and identity. Placing oneself in the “long timeline” of past histories and future aspirations can expand one’s temporal bandwidth, making one’s sense of self more “solid” or “weighty.” However, when contemplating “Who am I?” or “What should I do?” I often find myself entangled in the expectations and responsibilities of both past and future. These coordinates make my understanding of myself heavier and more definitive, yet they also induce unease.

In a society driven by speed and efficiency, I feel a deep anxiety: that by submitting to the dominion of speed, I might be invisibly dissolved into it. As Paul Virilio remarks in The Aesthetics of Disappearance, “You don’t have speed, you are speed” (p. 92). Technology has dissolved boundaries that once required gradual transitions, rendering life a continuous and accelerated flow of synchronized operations. This has culminated in what Virilio calls a “sensory frenzy,” where individuals are inundated by an endless barrage of information and desires. In this unrelenting carnival of stimuli, there is no room for reflection, no buffer for philosophical thought, faith, or contemplation of meaning.

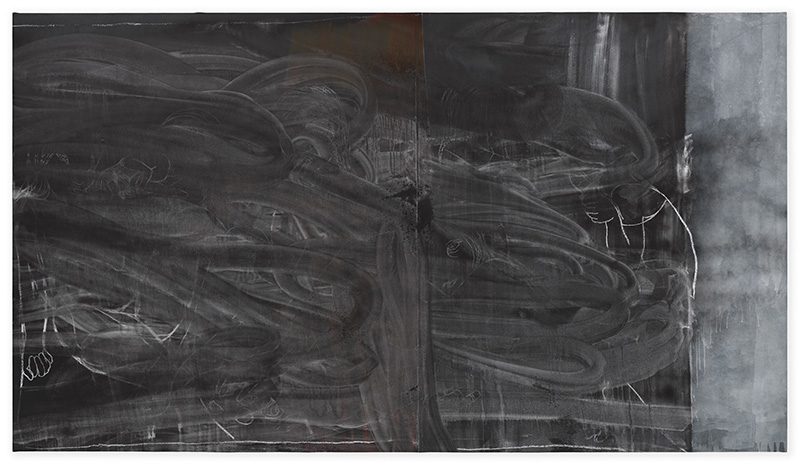

Rita Ackermann, The Wall Coming Down, 2014, © Rita Ackermann, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In response, I try to shed the externally imposed and technologized expectations of modern life and return to questioning the meaning of my own existence. By setting aside the promises of both past and future, I focus on the present. This mirrors Pynchon’s idea of narrowing temporal bandwidth to focus solely on the here and now. However, this “freedom” can paradoxically feel impoverished. One’s sense of presence weakens, self-positioning becomes unstable, and the absurd emerges—a world devoid of metaphysical meaning or grand narratives, yet met with silence when one searches for purpose.

This absurdity unfolds as Albert Camus describes in The Myth of Sisyphus:

“It happens that the stage sets collapse. Rising, street-car, four hours in the office or the factory, meal, street-car, four hours of work, meal, sleep, and Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday and Saturday according to the same rhythm—this path is easily followed most of the time. But one day the ‘why’ arises and everything begins in that weariness tinged with amazement. ‘Begins’—this is important. Weariness comes at the end of the acts of a mechanical life, but at the same time it inaugurates the impulse of consciousness.” (p. 5).

Confronted with the absurd and the vacuum of meaning it creates, I choose neither escape nor the weightless indifference that accompanies the dissolution of truth—a state Milan Kundera characterizes in The Unbearable Lightness of Being:

“In this world, everything is pardoned in advance and therefore everything cynically permitted.” (p. 4).

Without the constraints of metaphysical or socio-moral frameworks, boundaries once thought impassable begin to erode. This “lightness” renders behavior arbitrary and erodes the clarity of ethical norms. In this context, I see artistic creation and self-expression as ways to confront the absurd and unfold my own meaning. My paintings are not representations of specific locations, self-portraits, or visual depictions of my role in a given environment. Instead, they abstractly express my existence in the world, here and now. When I confront the world, I seek to unfold meaning from the absurd and the nihility. This ineffable pursuit and the inability to fully grasp meaning inevitably lead to abstraction in my work, while also evoking the postmodern sublime.

As Barnett Newman famously declared, “The sublime is now.” When all “reasons” and “futures” are canceled, I find myself suspended in a “pure present,” a fissure in which there is only one certainty: this world is absurd, time is meaningless, and we exist as a sublime presence within an absence. In such a “here-now” moment, both artist and viewer are cast into an indescribable, irrational void—simultaneously overwhelming. This experience may be understood as the “absurd sublime,” or as a state where purpose, causality, and meaning are entirely suspended.

Modern life is quotidian, often described as “everyday life,” yet it also signifies a way of living that is measurable and controllable. However, my artistic creation emerges from this ordinariness. My paintings do not depict the spectacular or extraordinary scenes often associated with romantic notions of the sublime—mountains, oceans, or storms. Instead, they delve into the everyday.

In my work, the sublime is no longer rooted in nature or sensory extremes. Edmund Burke’s psychological sublime highlights terror and aesthetic distance when faced with vast, incomprehensible power, while Kant’s sublime elevates reason and morality into the realm of the transcendent. My exploration, however, aligns with the postmodern sublime, which Jean-François Lyotard describes as “the presentation of the unpresentable.” Though such presentations ultimately fail and may even evoke pain, they contain an intangible sense of fulfillment (The Postmodern Condition, p. 12).

This “sublime” is not just an aesthetic concept but a way of challenging and overturning established orders through art. Yet in my practice, I do not seek to overthrow but rather to examine—to reflect on the self in the absence of order, within the absurd. My work embodies “the quixotic,” where all preconceptions are deconstructed: what is quantified becomes ungraspable, what is accelerated is paused, and what is imbued with meaning is suspended.

Lyotard writes in The Postmodern Condition:

“The postmodern would be that which, in the modern, puts forward the unpresentable in presentation itself; that which denies itself the solace of good forms… that which searches for new presentations, not in order to enjoy them but in order to impart a stronger sense of the unpresentable.” (p. 81).

This resonates with my intention for the audience. In our hyper-accelerated society, “good forms” abound—those easily understood, aesthetically pleasing, and assigned immediate value. These forms are rapidly produced and consumed, offering comfort to viewers: stories are resolved, styles are orderly, and truths are unveiled, suggesting a world that is explainable and coherent. My work rejects these “good forms.” It seeks instead to pause, to confront disorientation, to feel the absence of value, the silence of meaning. It invites the viewer to dwell in uncertainty, to experience discomfort, and, to unfold themselves in the absurd.

Course contexts

Reading Groups: Robert Storr on Gerhard Richter’s ‘October 18, 1977’

Dead

1988 62 cm x 62 cm Catalogue Raisonné: 667-2

Oil on canvas

When I was a child, I always believed that history existed to illuminate the truth of the past. It was not until a history teacher told me that history is never really about unearthing factual truth, but rather about understanding how people in the past believed in and interpreted certain events. This idea came back to me after viewing Gerhard Richter’s works and listening to Robert Storr’s commentary. The more we know, the more we realize how elusive truth can be: we attempt to piece together the “side stories” to reconstruct what happened, yet we still struggle to arrive at any final conclusion.

Richter’s own experience illustrates this complexity. On the one hand, he sympathized with the Baader-Meinhof Group’s desire for social change; on the other, he felt perplexed by their descent into violent extremism. He gathered a large number of news reports, forensic photos, and recollections from different groups, but ultimately chose not to advocate a particular political stance or produce a purely explanatory representation. Instead, he deliberately blurred these images, neither defending radical violence nor echoing any official narrative. By doing so, he created a sense of distance and uncertainty, prompting viewers to recognize how difficult it is to pin down a single, definitive truth. This approach starkly contrasts with the univocal narratives often found in traditional historical records. In effect, Richter urges us to question so-called “established facts and truths.”

This resonates with the postmodern concerns behind my own work. Postmodernism rejects the grand or “meta” narrative, favoring fragmented, reflective, and sometimes absurd modes of storytelling. As Jean-François Lyotard states in The Postmodern Condition, “The postmodern would be that which, in the modern, puts forward the unpresentable in presentation itself; that which denies itself the solace of good forms… the consensus of a taste which would make it possible to share collectively the nostalgia for the unattainable” (p. 81). To me, Richter’s blurred treatment of photographs exemplifies such a refusal of “good forms,” declining to provide a straightforward, readily digestible truth. Similarly, my abstract landscape paintings strive for an uncertain effect in which meaning cannot be grasped instantly. While my discussion is rooted in existentialist thought—how confronting the absurd often renders us powerless to fully grasp our existence—Richter’s perspective comes from politics, memory, and the re-presentation of past “truth.” Even seemingly clear political positions become complicated by the unstable, malleable nature of memory and the ways in which events are continually rewritten. This encourages viewers to stay alert and to critically assess every seemingly coherent or emotionally charged “truth” in everyday life. As we often discuss in our reading group, in such a complex and uncertain world, perhaps the best we can do is remain keenly aware, stay open-minded, yet maintain a careful distance.

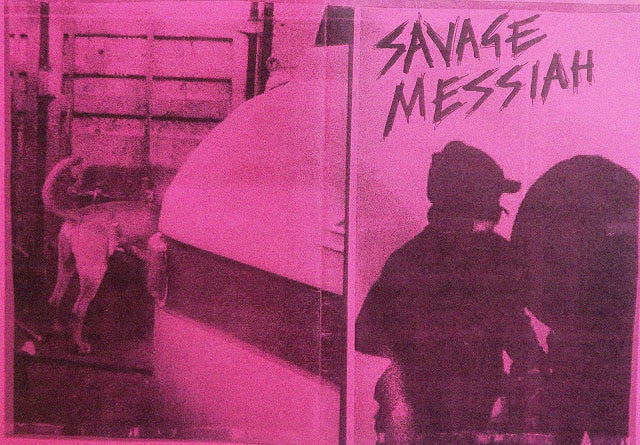

Reading Groups: Laura Grace Ford: We Move Amongst Ghosts

In both the article “We move amongst ghosts” and our reading group discussion, the central focus is on how late 20th-century neoliberal policies in London led to the capitalization, homogenization, and gentrification of the urban environment. These forces have squeezed out public spaces and marginalized small communities, leaving social relations ever more atomized. Through her independent zine Savage Messiah, artist Laura Grace Ford documents and critiques the complex social contradictions arising under neoliberalism, finance capital, and the rhetoric of “redevelopment.”

In my view, a major cause behind these issues is capital’s relentless pursuit of “efficiency.” When efficiency becomes paramount, the same model is replicated throughout the city, crowding out diverse voices and eroding the spaces required for different eras and cultures to flourish. The article’s mention of “ghost spaces” and drifting along the “urban edges” represents a resistance to such homogenization and efficiency-driven logic. It reminds me of Michel de Certeau’s concept of “tactic” in The Practice of Everyday Life: ordinary or marginalized individuals engage in agile, subversive actions—“guerrilla” practices of everyday life—to carve out small but persistent forms of resistance or reinterpretation within what seems to be a rigid urban framework.

Reflecting on urban issues also brings to mind the homogenization that occurs in tourist sites in my own hometown. In order to achieve the coveted 5A rating, a scenic spot must comply with rigid standards: a signature gate, a reception area, food and entertainment facilities, and so on. Consequently, most sites look virtually identical, and even the snacks and souvenirs are much the same from one place to another. Worse still, some natural scenic areas are awkwardly fenced in, turning what was once an open natural landscape into a closed-off “garden” for viewing. I believe the culprit here is also a drive for minimal cost and maximum efficiency: transforming a site into a high-grade attraction as quickly as possible to lure visitors and generate revenue. This streamlined approach closely parallels the gentrification of cities like London, and it’s happening in many tourist-oriented towns as well: buildings facing main roads are veneered in modern façades to satisfy tourists’ photo and social media needs, while locals often continue to live in “ghost regions” hidden behind the scenes, rarely acknowledged on social platforms.

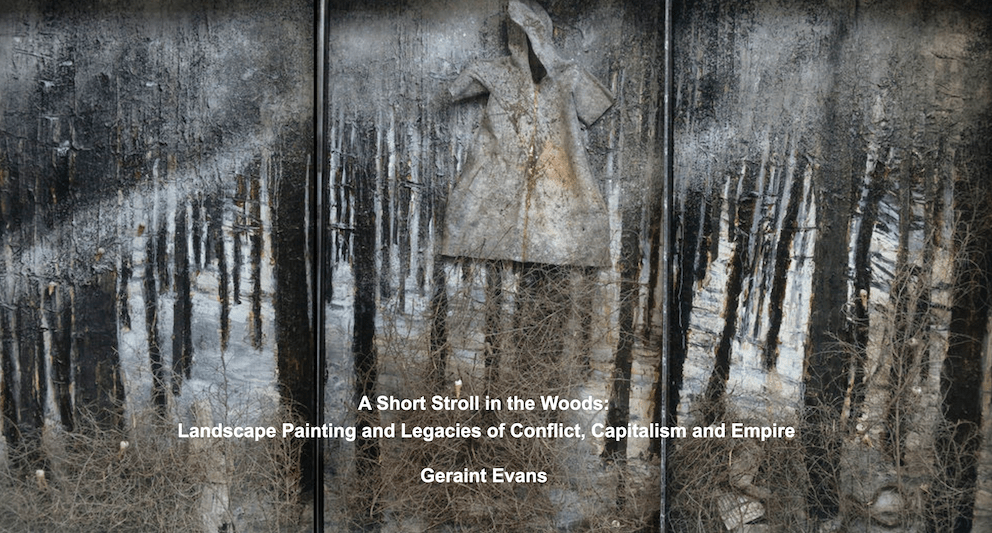

Painters’ forum: A Short Stroll in the Woods: Landscape Painting and Legacies of Conflict, Capitalism and Empire

The lecture, A Short Stroll in the Woods: Landscape Painting and Legacies of Conflict, Capitalism and Empire, reveals the multifaceted nature of landscape art. Landscape is no longer merely a symbol of natural beauty or pastoral idyll, but instead carries layers of war trauma, political ideology, national identity, and postcolonial critique. Through examples spanning different countries, continents, and historical periods, the lecture uncovers the historical and ideological significance hidden behind each work. For instance, Anselm Kiefer’s paintings often engage with national mythologies and ideological narratives. Meanwhile, John Constable’s renowned The Haywain conceals, beneath its seemingly tranquil pastoral scene, the social turmoil sparked by the Enclosure Acts and the difficulties faced by farmers under new land policies. Similarly, the majestic landscapes of the American West, created during the era of frontier expansion, overlook the presence of Indigenous peoples, underscoring an ironic tension between “cultivating nature” and “depicting nature.” Later works dealing with the aftermath of global wars further demonstrate that landscape painting is not just about representing scenic vistas, but also bears deeper significance in its historical context—both in what it depicts and what it leaves out.

My personal interest in traditional landscape painting stems from my current practice, which could be labeled as “abstract landscape.” Rather than depicting recognizable mountains, rivers, or other tangible subjects, I focus on expressing inexpressible emotions, ambiguous meanings, and a confluence of multiple elements. This shift poses a creative challenge: when meaning becomes elusive and the imagery more abstract, can such expressionistic painting still be called “landscape art”? Suppose I paint an abstract piece inspired by my daily life in London, where the overall palette is tinged in gray, interspersed with layered rectangular shapes and assorted colors, yet devoid of any clearly identifiable symbols or references—do viewers necessarily require a fixed thread or key to decipher it? Must there be a distinct “cause” or rationale that unlocks the concept of “landscape” in the work? These are the questions I continually grapple with in my own creative process.

References

Camus, A. (1942). The Myth of Sisyphus. Éditions Gallimard.

M Kundera (1999). The unbearable lightness of being. London ; Boston: Faber And Faber.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1982). PRESENTING THE UNPRESENTABLE: THE SUBLIME. [online] Artforum. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/features/presenting-the-unpresentable-the-sublime-208373/.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1984). The Postmodern condition: a Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Newman, B., & Strick, J. (1994). The sublime is now: the early work of Barnett Newman; paintings and drawings 1944-1949. New York: Pace/Wildenstein.

Pynchon, T. (2013). Gravity’s rainbow. London: Vintage.

Slocombe, W. (2013). Nihilism and the sublime postmodern. Routledge.

Virilio, P. (1991). The Aesthetics of Disappearance. Semiotext(e).